How long do northern lights usually last?

How Long Do the Northern Lights Usually Last?

One of the most common questions from aspiring aurora chasers is about timing: ‘If I see them, how long will they stick around?’ The answer is as dynamic as the lights themselves. The Northern Lights are not a static phenomenon; they are a live performance put on by the Sun and Earth’s atmosphere, and the length of the show can be unpredictable.

While many displays are fleeting, lasting just long enough for a few breathtaking photos, others can fill the sky with dancing light from dusk until dawn. Understanding the factors that influence an aurora’s duration can help you manage expectations and maximize your chances of witnessing a truly unforgettable spectacle.

Understanding Aurora Duration: From Minutes to Hours

The length of an aurora display is directly tied to the behavior of the solar wind hitting Earth. Think of it like a fire: a small, quick gust of wind might cause a brief flare-up, while a steady, strong wind can keep the fire roaring for hours.

The Typical Display: 15-30 Minutes

For most observers, a typical, memorable aurora display is part of an event called a geomagnetic substorm. This is a relatively short, intense burst of energy released into the atmosphere. The display often starts as a simple, faint arc across the sky. As the substorm peaks, this arc can suddenly brighten and explode into dynamic, fast-moving curtains and rays of light. This peak activity, the most ‘active’ and photogenic part of the show, usually lasts for 15 to 30 minutes. Afterward, the lights may fade back into a quiet arc or disappear entirely as that specific injection of energy subsides.

The Brief Flicker: A Few Minutes

Sometimes, the conditions for an aurora are only marginally met. The solar wind might be weak, or its magnetic field orientation might be unfavorable for energy transfer. In these cases, you might only witness a brief flicker of auroral activity lasting just a few minutes. This can manifest as a faint, greyish-green glow on the horizon that is barely visible to the naked eye, or a short-lived patch of light that quickly dissipates. These minor events are very common but are often missed by casual observers. They represent the constant, low-level interaction between the solar wind and our planet’s magnetic shield.

The All-Night Spectacle: Several Hours

The holy grail for aurora hunters is the all-night display. These long-lasting events are powered by major solar events, most notably a Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) or a high-speed solar wind stream. When one of these hits Earth, it provides a powerful, continuous flow of energy into the magnetosphere for many hours. This results in a major geomagnetic storm. During such a storm, the aurora can remain active and dynamic for the entire night, going through multiple cycles of brightening, dancing, and fading, only to roar back to life again. These are the events that bring the aurora to lower latitudes and create the most awe-inspiring memories.

Key Factors Influencing Aurora Longevity

The duration of the aurora isn’t random. It’s governed by specific conditions in space weather, primarily the characteristics of the solar wind arriving at Earth.

Solar Wind and the ‘Southward Bz’

The single most important factor for a strong, long-lasting aurora is the orientation of the Interplanetary Magnetic Field (IMF), which is carried by the solar wind. Specifically, its north-south component, known as ‘Bz’. When the Bz is oriented southward (negative), it effectively ‘opens a door’ in Earth’s magnetosphere, allowing vast amounts of energy and particles to flow in. A strong and sustained southward Bz is the primary ingredient for a geomagnetic storm that can fuel the aurora for hours. If the Bz is northward (positive), the ‘door’ is mostly closed, and any auroral activity will be weak and short-lived.

The Role of Earth’s Rotation

From a fixed location on the ground, the duration of a display can also be influenced by Earth’s rotation. The aurora occurs in a giant ring around the magnetic pole called the auroral oval. This oval is generally fixed in place relative to the Sun. As the Earth rotates underneath it, your location on the ground moves into, through, and out of the most active part of this oval. The peak viewing time is typically around magnetic midnight (roughly 10 PM to 2 AM), when your location is under the most active, night-side portion of the oval. This is why a display might seem to fade late at night, simply because your viewing spot has rotated out of the prime zone.

The Dynamic Nature of a Display

Even during a long-lasting storm, the aurora is rarely constant. It’s important to understand that the lights ‘breathe’—they have their own rhythm of brightening and fading.

Ebbs and Flows

An aurora display is not a steady light. It is constantly changing in brightness, shape, and intensity. During a multi-hour event, it’s common to experience periods of intense, fast-moving coronas and curtains, followed by lulls where the light softens to a diffuse glow or a simple arc. Patience is key. Many novice aurora watchers make the mistake of leaving during a quiet period, only to miss a spectacular outburst an hour later. If a strong storm is forecast, it’s worth waiting through the lulls, as the show is likely not over. These ebbs and flows are the natural cycle of energy being stored and released in Earth’s magnetotail.

Quick Facts

- A typical aurora display, or ‘substorm’, lasts for 15-30 minutes.

- Major geomagnetic storms caused by CMEs can produce auroras that last for many hours.

- The duration is primarily controlled by the strength and consistency of the solar wind.

- A sustained southward Bz component of the Interplanetary Magnetic Field is crucial for long-lasting displays.

- The best viewing time is often around magnetic midnight (10 PM – 2 AM local time).

- Aurora displays are dynamic; they naturally brighten and fade in cycles.

- Even on a quiet night, you might see a brief flicker of auroral light lasting only a few minutes.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Do the Northern Lights happen every night? A: Yes, the aurora is almost always present somewhere within the auroral oval. However, its visibility from the ground depends on your location, clear skies, darkness, and the current level of geomagnetic activity.

Q: Can an aurora display stop and then start again? A: Absolutely. It is very common for a display to fade away for 30 minutes to an hour, only to return with another brilliant burst of activity. This is part of the natural cycle of substorms during a period of heightened activity.

Q: If the forecast is strong, am I guaranteed to see them all night? A: Not necessarily. A strong forecast increases the probability of a long-lasting event, but the timing and intensity can still be unpredictable. The solar wind is turbulent, and conditions can change, causing the aurora to fluctuate in strength throughout the night.

Other Books

- NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center – Aurora Dashboard

- University of Alaska Fairbanks – What is a Substorm?

- Space.com – Aurora Borealis: What Causes the Northern Lights & Where to See Them

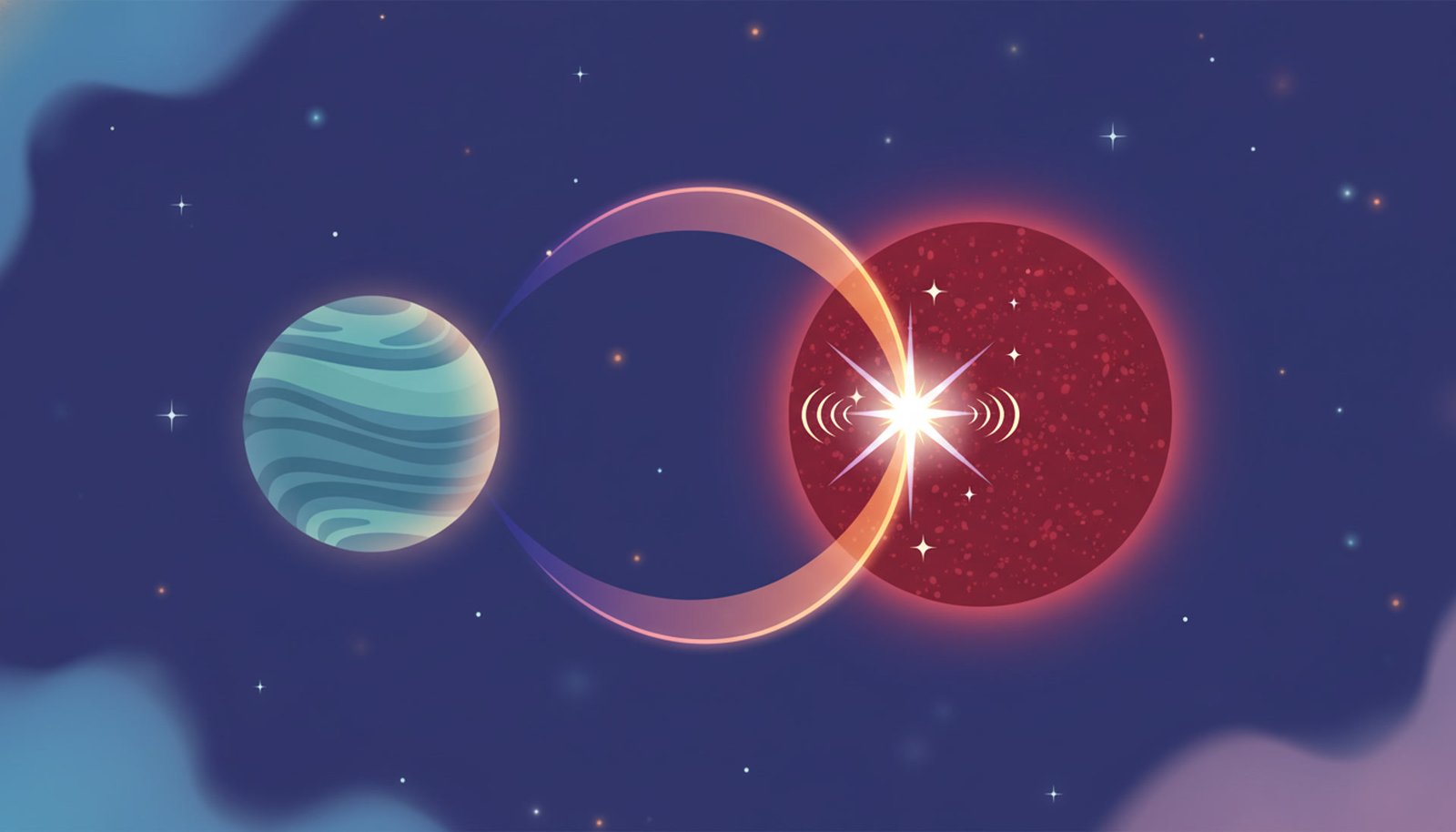

Stars That 'Sing' for Their Planets

Summary

By the end of this article, you will understand how a planet can create a radio signal on its host star, and how scientists use this ‘auroral footprint’ to hunt for exoplanets and their crucial magnetic fields.

Quick Facts

- Surprise: We're not listening to the planet, but to the star's radio 'shout' caused by the planet.

- The TRAPPIST-1 system of seven planets is a prime target for this type of radio detection.

- This phenomenon is a scaled-up version of the interaction between Jupiter and its volcanic moon, Io.

- A planet's magnetic field is a key ingredient for protecting a potential atmosphere and enabling life.

- The radio signal would pulse in time with the planet's orbit, like a cosmic lighthouse.

The Discovery: Tuning In to a Star's Echo

How do you find a planet that’s too small and quiet to detect directly with a radio telescope? A team at the University of Leicester came up with a clever solution. Their Story is one of inspiration. They looked at our own solar system, specifically at Jupiter and its moon Io. Io’s movement through Jupiter’s magnetic field creates a powerful electrical circuit, leaving a glowing auroral ‘footprint’ in Jupiter’s atmosphere. The researchers theorized that exoplanets orbiting close to M-dwarf stars could do the same thing on a much grander scale. They built a model to calculate the energy transferred from the planet to the star and predicted the strength of the resulting radio signal. Their work identifies 11 specific systems that might be ‘singing’ right now, waiting to be heard.

Original Paper: ‘Exoplanet-Induced Radio Emission from M-Dwarfs’ by Turnpenney et al.

A region of emission analogous to the Io footprint observed in Jupiter’s aurora is produced.

— Sam Turnpenney et al.

The Science Explained Simply

Imagine a river: the stellar wind flowing from the star. Now, put a rock in it: the exoplanet. Normally, the wake flows downstream. But if the river flows slower than the speed of ‘sound’ in that medium (the Alfvén speed), something amazing happens: the disturbance can travel upstream. This is a sub-Alfvénic interaction. This is NOT the planet beaming radio signals into space. Instead, the planet’s presence creates a disturbance in the star’s magnetic field, forming two ‘Alfvén wings’ that act like cosmic wires. These wires carry energy back to the star’s surface. When that energy arrives, it accelerates electrons in the star’s atmosphere, which then release that energy as a focused beam of radio waves.

Energy can be transported upstream of the flow along Alfvén wings.

— NorthernLightsIceland.com Team

The Aurora Connection

The phenomenon described in the paper is a direct cousin to the auroras we see on Earth and Jupiter. The ‘Io footprint’ on Jupiter is a persistent auroral spot caused by the magnetic connection to its moon. This research predicts a similar ‘exoplanet footprint’ on M-dwarf stars. For a planet to create this effect, it needs either a protective magnetic field or a thick atmosphere to act as an obstacle. Therefore, detecting this radio signal is a powerful clue that the planet has a magnetic shield. That shield is the single most important factor in protecting an atmosphere from being stripped away by the stellar wind—a prerequisite for life as we know it and for any planet to host its own auroras.

A Peek Inside the Research

This wasn’t just a guess; it was a feat of calculation. The researchers used a model of stellar wind (the Parker spiral) to determine the plasma conditions around the star. They then calculated the ‘Poynting flux’—the amount of energy carried along the Alfvén wings. Finally, they estimated how much of that energy would be converted into radio waves by the electron-cyclotron maser instability (ECMI). To make their predictions, they had to estimate planetary properties, like magnetic field strength, using scaling laws. They ran these calculations for 85 known exoplanets orbiting M-dwarfs to create a priority list for radio telescopes like the VLA and the future SKA, turning a theoretical idea into a concrete observation plan.

Key Takeaways

- Planets moving through stellar wind can send energy 'upstream' to their star.

- This energy transfer happens along magnetic 'Alfvén wings'.

- The energy hitting the star's atmosphere can trigger a powerful radio burst via the ECMI mechanism.

- This method allows us to potentially detect Earth-sized planets and measure their magnetic fields.

- M-dwarf stars are ideal targets because their habitable zones are very close, strengthening the interaction.

Sources & Further Reading

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: So, are we listening to aliens?

A: No, we are not listening for intelligent communication. We are listening for a natural radio emission caused by the physical interaction between a planet and its star, similar to how Jupiter’s moons create auroras.

Q: Why can’t we just listen to the planet’s own radio signal?

A: For Earth-sized planets, the radio signals they might produce are at very low frequencies. These signals get trapped by the planet’s own ionosphere and can’t escape into space for us to detect. This indirect method bypasses that problem by having the much more powerful star do the broadcasting.

Q: Does this mean these planets have life?

A: Not directly, but it’s a huge step. A strong magnetic field is essential for protecting a planet’s atmosphere, which is a key requirement for habitability. Finding a magnetic field would be a very promising sign.