How long does northern lights strain take to grow?

How Long Do the Northern Lights Last?

When searching for information on the ‘Northern Lights’, it’s common to encounter two very different topics: the breathtaking natural light show in the sky (Aurora Borealis) and a well-known cannabis strain. This article focuses exclusively on the natural celestial phenomenon.

One of the most common questions for aurora chasers is, ‘Once they appear, how long will they stick around?’ The answer is not simple, as the duration of an aurora display is as variable as its shape and color. Understanding the forces that drive the aurora helps explain why some shows are brief flashes while others are epic, all-night events.

Understanding Aurora Duration

The length of an aurora display is directly tied to the space weather conditions causing it. Think of it like a celestial faucet: the longer the solar wind ‘faucet’ is turned on and pointed at Earth, the longer the light show will last.

Typical Display Timespan

For a casual observer, a typical auroral ‘substorm’ or burst of activity often lasts between 15 and 40 minutes. During this time, the lights can go from a faint, static arc to a vibrant, dancing curtain of light that fills the sky. It’s common for the aurora to appear, put on a spectacular show, and then fade away, sometimes returning later in the night if conditions persist. Many aurora hunters pack their patience, as a quiet sky can erupt with light with little warning. It’s not a continuous event like a sunset; it’s a series of dynamic, often unpredictable, bursts of light.

Factors Influencing Duration

The primary factor determining how long the Northern Lights last is the solar wind streaming from the Sun. Specifically, the orientation of the interplanetary magnetic field (IMF) carried by the solar wind is crucial. When the IMF is oriented southward (a negative ‘Bz’ value), it efficiently connects with Earth’s magnetosphere, allowing energy to pour in. As long as this southward Bz condition persists, the aurora can continue. A strong, long-lasting stream of solar wind, such as from a coronal hole high-speed stream or a Coronal Mass Ejection (CME), can create intense auroras that last for many hours or even across multiple nights.

All-Night Auroras: Geomagnetic Storms

The most spectacular, long-lasting displays occur during geomagnetic storms. These are major disturbances of Earth’s magnetosphere caused by a powerful CME hitting our planet. During a strong storm (e.g., G3 or higher on the NOAA scale), the aurora can be visible for the entire night, from dusk until dawn. The display will ebb and flow in intensity, with multiple powerful substorms creating waves of activity. These are the events that allow the aurora to be seen at much lower latitudes than usual and provide the hours-long light shows that photographers and sky-watchers dream of.

Clarifying the 'Northern Lights' Name

It’s important to clarify that this website discusses the astronomical phenomenon. The term ‘Northern Lights’ has been adopted by others, which can cause confusion.

The Natural Wonder: Aurora Borealis

The Aurora Borealis, or Northern Lights, is a natural light display in Earth’s sky, predominantly seen in high-latitude regions. It is caused by collisions between energetic particles (electrons and protons) from the sun, carried by the solar wind, and gas particles in our own upper atmosphere. These collisions excite the gas atoms, causing them to emit light of different colors, most commonly green. This is a phenomenon of physics and astronomy, studied by agencies like NASA and NOAA. It is a beautiful, harmless, and awe-inspiring spectacle.

A Note on the Cannabis Strain

There is also a famous strain of cannabis named ‘Northern Lights’. It was named for its desirable characteristics, but it has no physical or scientific connection to the actual Aurora Borealis. Information regarding its cultivation, growth time, or effects is entirely unrelated to the study of auroras. For details on that topic, one would need to consult specialized horticultural or cannabis-specific resources. This website is dedicated solely to the science and wonder of the natural light show in our planet’s polar skies.

Quick Facts

- A typical aurora burst lasts for about 15-40 minutes.

- Major geomagnetic storms can produce aurora displays that last all night.

- The duration is controlled by the solar wind and the orientation of its magnetic field (Bz).

- A persistent ‘southward Bz’ is the key ingredient for a long-lasting aurora.

- The term ‘Northern Lights’ can refer to the Aurora Borealis or a cannabis strain; this article is about the natural phenomenon only.

- Aurora displays are not continuous; they often occur in waves or bursts of activity.

- Patience is key for aurora watching, as a quiet sky can become active later in the night.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Is there a best time of night to see a long-lasting aurora? A: While auroras can happen at any time during darkness, the most active periods are often centered around ‘magnetic midnight’, which is typically between 10 PM and 2 AM local time. This is when you are most likely to be under the most active part of the auroral oval.

Q: How can I know if an aurora display is likely to be long? A: You can monitor space weather forecasts from sources like the NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center. Look for alerts about incoming CMEs or high-speed solar wind streams, and check the real-time Bz value. A strong, sustained negative Bz value suggests conditions are ripe for a long display.

Q: Does the aurora ‘use up’ its energy and fade? A: Yes, in a way. An auroral substorm is a process where the magnetosphere releases built-up energy from the solar wind. Once that energy is discharged as an aurora, things may quiet down until more energy is loaded into the system, which can then trigger another display.

Other Books

- NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center – Official Forecasts

- SpaceWeatherLive – Real-time Auroral and Solar Data

- University of Alaska Fairbanks – Geophysical Institute FAQ

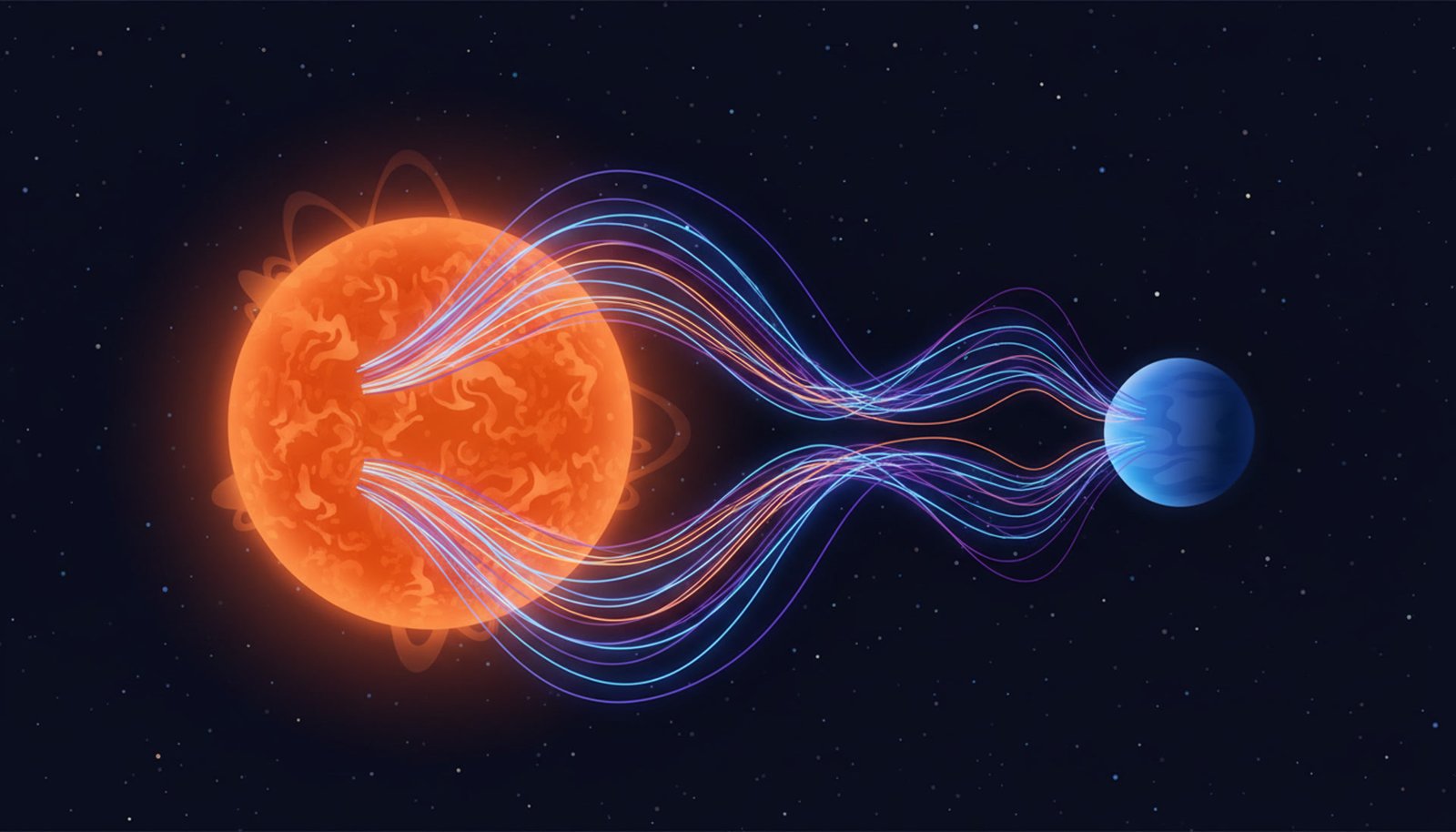

Cosmic Tug-of-War: Magnetic Fields Move Worlds

Summary

By the end of this article, you will understand the invisible magnetic web that connects stars and planets, a force so powerful it can create cosmic shocks, cause stellar storms, and even drag entire planets out of their orbits.

Quick Facts

- A planet orbiting close enough to its star moves through a dense magnetic 'atmosphere', creating a shockwave like a boat moving through water.

- This magnetic connection can transfer enough energy to create a bright 'hot spot' on the star's surface that follows the planet's orbit.

- The magnetic drag is so strong it can cause planets to migrate, either spiraling into their star or being pushed further away over millions of years.

- A planet's own magnetic field acts like a shield; its orientation (north pole up or down) drastically changes the strength of the interaction.

- Astronomers have noticed a 'dearth' of close-in planets around fast-rotating stars, possibly because this magnetic interaction has already pulled them into the star.

The Discovery: More Than Just Gravity

When astronomers began discovering thousands of ‘hot Jupiters’—gas giants orbiting incredibly close to their stars—they found phenomena that gravity alone couldn’t explain. The Story began with puzzling observations: some host stars showed strange, synchronized flare-ups, while others seemed to have ‘cleared out’ zones with no close-in planets. Scientists realized these planets were so close they were orbiting *inside* the star’s extended magnetic field. This triggered a wave of research into star-planet magnetic interaction (SPMI). The models reviewed in this paper show how this interaction can explain the mysteries: planets ‘poking’ their stars to cause flares, and a magnetic ‘drag’ so powerful it could make planets spiral to their doom, explaining the empty zones.

Original Research Paper: ‘Models of Star-Planet Magnetic Interaction’

Magnetic interactions are today a serious candidate to explain these fascinating phenomena.

— Antoine Strugarek, Astrophysicist

The Science Explained Simply

Imagine a planet so close to its star that the star’s magnetic field is stronger than the stellar wind pushing outwards. This is the sub-Alfvénic regime. Now, this isn’t just a static field; it’s a dynamic plasma environment. As the planet orbits, it plows through this magnetic medium, creating a disturbance. The key concept is the Alfvén Wing. Instead of the disturbance spreading out, the energy gets focused and channeled along the magnetic field lines, creating two ‘wings’ that connect back to the star. This is NOT like a simple magnetic attraction. It’s an active, energetic connection that transfers momentum and power, acting like both a brake and a generator. It’s a constant, powerful interaction driven by the planet’s motion.

A close-in planet can be viewed as a perturber orbiting in the likely non-axisymmetric inter-planetary medium.

— Antoine Strugarek, Astrophysicist

The Aurora Connection

The beautiful auroras on Earth happen when the solar wind interacts with our planet’s magnetic field, channeling energy and particles into our atmosphere. Star-planet magnetic interaction is this exact process, scaled up to an incredible degree. The Alfvén wings are like the magnetic field lines that guide particles to Earth’s poles, but they carry vastly more energy. When this energy slams back into the star’s atmosphere, it can create a starspot—a stellar aurora. When it hits the planet’s atmosphere, it can trigger planetary auroras that would be thousands of times more powerful than our own. Studying these extreme interactions helps us understand the fundamental physics that protects Earth’s atmosphere and gives us our own gentle light shows.

A Peek Inside the Research

Modeling these interactions is incredibly hard. Early researchers used clever analogies, like treating the star-planet system as a simple electric circuit (the ‘unipolar inductor’ model). The planet’s motion acted as a generator, the magnetic field lines were the wires, and the planet and star were resistances. While useful, this was too simple. The real progress came from 3D magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) simulations. These are complex computer models that treat the star’s wind as a magnetized fluid. Researchers spend immense effort creating realistic ‘boundary conditions’ for the planet and star to ensure the simulation is accurate. These models, like those shown in the paper, are the tools that allow us to visualize the invisible magnetic games playing out between stars and their planets.

Key Takeaways

- Gravity isn't the only major force in solar systems; star-planet magnetic interaction (SPMI) is critical for close-in planets.

- 'Alfvén wings' are channels of energy that flow along magnetic field lines between a star and a planet, similar to a current in a wire.

- The interaction depends on whether the planet is magnetized ('dipolar') or not ('unipolar'). A magnetized planet has a shield, a non-magnetized one gets permeated.

- Observing the effects of SPMI, like pre-transit dips in starlight, could be one of the best ways to detect magnetic fields on distant exoplanets.

- These magnetic forces can heat planets, strip their atmospheres, and influence their entire evolutionary path.

Sources & Further Reading

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Can this magnetic interaction happen between the Sun and Earth?

A: Yes, but it’s much, much weaker. Earth is far outside the Sun’s sub-Alfvénic zone, where the solar wind dominates. The interactions described in the paper are for exoplanets orbiting hundreds of times closer to their star than Earth does to the Sun.

Q: Can we actually see these magnetic fields?

A: Not directly, but we can see their effects. We can look for synchronized stellar flares, absorption of starlight from a planet’s bow shock just before it transits, or radio emissions from the planetary aurorae. These are the observable clues that tell us the magnetic interactions are happening.

Q: Could this force eventually destroy a planet?

A: Absolutely. The magnetic torque can cause a planet’s orbit to decay, making it spiral closer and closer to its host star until it’s consumed. This is a leading theory for why we don’t find many planets in extremely close orbits around certain types of stars.