When are northern lights tonight?

How Can I Predict the Northern Lights Tonight?

The question ‘Can I see the Northern Lights tonight?’ is one of the most common, but the answer is never a simple yes or no. Seeing the aurora is a magical experience that depends on a perfect alignment of space weather and Earth’s local weather. It’s not about a set schedule; it’s about knowing what to look for.

This guide will empower you to become your own aurora forecaster. We’ll break down the three essential ingredients you need for a successful viewing and introduce you to the simple, powerful tools that experts use to predict when and where the celestial dance will begin.

The Three Essential Ingredients for an Aurora Sighting

For the Northern Lights to be visible, three distinct conditions must be met simultaneously. If even one of these is missing, your chances of seeing the aurora drop to nearly zero. Think of it as a three-item checklist for your aurora hunt.

1. Strong Geomagnetic Activity (The Aurora Forecast)

The aurora is caused by activity from the sun, and we measure this activity using the Kp-index. This is a global scale from 0 (calm) to 9 (extreme geomagnetic storm). For most people living in the northern United States, UK, or central Europe, a Kp-index of at least 4 or 5 is needed for the aurora to be visible on the horizon. In prime aurora locations like Iceland or northern Norway, a Kp of 1 or 2 can be enough for a good show. You can find the current and predicted Kp-index on websites like NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center or through dedicated mobile apps. A higher Kp-index means a stronger, more dynamic, and more widespread aurora.

2. A Dark, Clear Sky (Weather and Location)

This is the most straightforward but often most frustrating factor. The aurora occurs 60-200 miles up in the atmosphere, far above any clouds. If there is heavy cloud cover, you will not see the lights, no matter how strong the storm is. Always check your local weather forecast for cloud cover predictions for the hours between 10 PM and 2 AM. Additionally, you must escape light pollution. City and even suburban lights create a glow that will wash out all but the most intense auroral displays. Use a light pollution map to find a dark spot with a clear view of the northern horizon, at least a 20-30 minute drive away from any significant light sources.

3. The Right Time of Night (And Year)

While a strong storm can be visible after sunset, the prime viewing window is typically during the darkest part of the night, between 10 PM and 2 AM local time. This is when the sky is at its darkest, allowing your eyes to fully adjust and perceive the aurora’s faint colors. Another factor is the moon phase. A bright full moon acts like a giant source of light pollution, making it much harder to see the aurora’s details and colors. The best nights will always be around the new moon. Seasonally, the best times are during the months surrounding the equinoxes (September-October and March-April), as solar activity often increases during these periods.

Your Aurora Forecasting Toolkit

You don’t have to guess. Several free and powerful tools can give you a clear picture of your chances for any given night. Using a combination of these resources will give you the best possible prediction.

Real-Time Ovation Models

For the most accurate ‘right now’ forecast, nothing beats the aurora ovation models provided by organizations like NOAA. These are maps that show a 30-to-60-minute forecast of the aurora’s current intensity and location. The map displays a glowing green, yellow, and red oval over the polar regions. If you see that oval stretching down over your location on the map, and your skies are clear and dark, you should go outside immediately. This is the single most reliable tool for answering the ‘tonight’ question, as it’s based on real-time data from satellites monitoring the solar wind.

Essential Apps and Websites

Several user-friendly apps and websites consolidate all the necessary data into one place. Apps like My Aurora Forecast & Alerts and Glendale App are popular choices. They provide the current Kp-index, short-term and long-term forecasts, cloud cover maps, and solar wind data. Most importantly, you can set up push notifications that will alert you when the Kp-index reaches a certain level for your location. This means you don’t have to constantly check the data; your phone can tell you when it’s time to head out. Websites like SpaceWeatherLive and NOAA’s SWPC are excellent desktop resources for more detailed data and expert analysis.

Quick Facts

- You need three things to see the aurora: a high Kp-index, dark skies, and clear weather.

- The Kp-index measures geomagnetic activity on a scale of 0-9; a Kp of 4 or higher is often needed for mid-latitudes.

- The best viewing time is typically between 10 PM and 2 AM local time.

- Use NOAA’s 30-minute aurora forecast for the most accurate real-time view of aurora activity.

- City light pollution and a bright full moon can significantly reduce aurora visibility.

- Mobile apps like ‘My Aurora Forecast’ can send you alerts when activity is high.

- Even with a perfect forecast, local cloud cover is the ultimate deciding factor.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What Kp-index do I need to see the aurora from my location? A: This depends entirely on your latitude. In the Arctic Circle (e.g., Tromsø, Fairbanks), a Kp of 1-2 is often visible. In the northern US or UK, you’ll likely need a Kp of 4-6. For rare sightings in mid-latitude states, a major storm of Kp 7 or higher is required.

Q: How reliable are long-term aurora forecasts? A: Forecasts more than 2-3 days out are highly speculative. They are based on observing sunspots that might produce an eruption. The most reliable predictions are within a 24-48 hour window, after a Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) has actually left the sun and is heading toward Earth.

Q: Can I see the Northern Lights in a city? A: It is extremely difficult. City light pollution creates a bright skyglow that will wash out all but the most intense, once-in-a-decade auroral storms. For the best experience, you should always plan to drive to a dark location away from city lights.

Q: Why does my camera see the aurora better than my eyes? A: Camera sensors are more sensitive to light than the human eye. They can use a long exposure (leaving the shutter open for several seconds) to collect more light, revealing vibrant colors and details that may appear as faint, greyish clouds to the naked eye, especially during weaker displays.

Other Books

- NOAA SWPC – Aurora 30-Minute Forecast

- SpaceWeatherLive – Real-time Aurora and Solar Data

- NASA – What is Space Weather?

Earth's Magnetic Shield Breathes

Summary

By the end of this article, you will understand a powerful and simple new way to think about space weather: that Earth’s magnetosphere physically expands and contracts like it’s breathing, and how this simple idea explains the complex relationship between magnetic storms, substorms, and the aurora.

Quick Facts

- Surprise: A substorm, often seen as part of a storm, can actually weaken the main magnetic storm by rapidly releasing energy.

- It takes the auroral oval about 45 minutes to expand after the solar magnetic field turns south, but 8 hours to contract after it turns north.

- The model predicts that during long periods of calm, 'dents' should form on the pre-noon and post-noon sides of our magnetic shield.

- The mysterious 'theta aurora', a glowing bar across the polar cap, can be explained by a severely contracted magnetosphere splitting the magnetotail.

The Discovery: Solving a Cosmic Puzzle

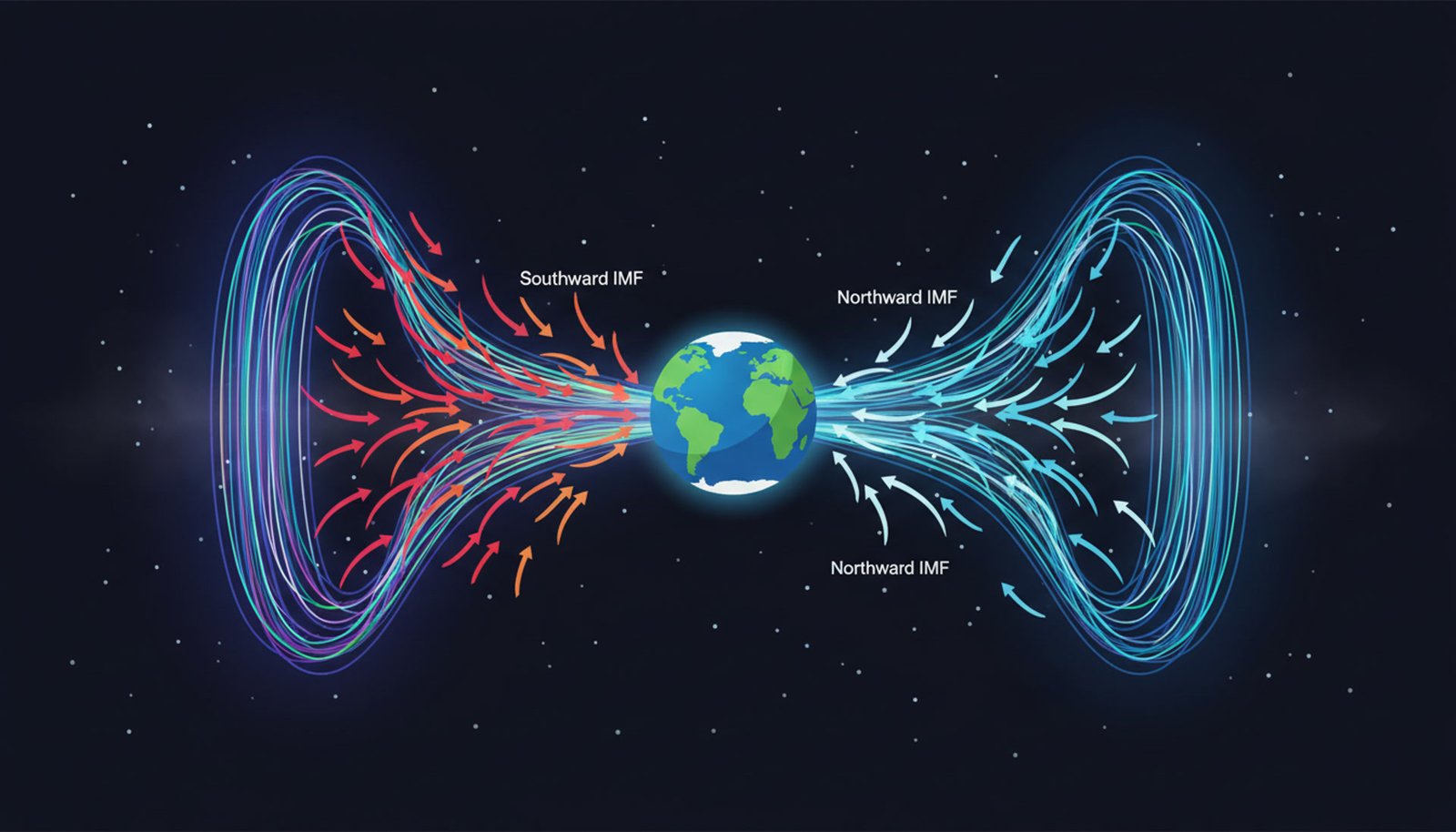

For decades, scientists have used a complex model called ‘magnetic reconnection’ to explain space weather. But some observations never quite fit, like why the main phase of a magnetic storm begins *before* the first substorm, or why substorms can sometimes weaken a storm. This research proposes a simpler Story: what if the magnetosphere behaves like a simple physical object? The paper shows that by treating the interaction as an attraction or repulsion—like two magnets—many of these puzzles disappear. A southward Interplanetary Magnetic Field (IMF) attracts and expands Earth’s field, creating a storm. A northward IMF repels and contracts it. This ‘breathing’ model provides an intuitive framework that matches observations without the theoretical problems of older models.

Original Paper: ‘Magnetic Storm-substorm Relationship and Some Associated Issues’ by E. P. Savov

The expansion (contraction) of magnetosphere accounts for the observed expansion (contraction) of the auroral oval.

— E. P. Savov, Researcher

The Science Explained Simply

Imagine the Sun sends out a magnetic field (the IMF). When the IMF arriving at Earth points south, its field lines align with Earth’s in an attractive way. This pulls Earth’s magnetic shield outward, expanding it and allowing it to capture more energy and particles from the solar wind. This is the ‘growth phase’ of a storm. Now, let’s build a fence: this is NOT the same as ‘magnetic reconnection’ where field lines are thought to break and re-form. Think of it more as a balloon inflating. Conversely, when the IMF points north, the fields repel each other. This squeezes and contracts the magnetosphere, pushing the solar wind away more effectively and leading to calmer space weather. The Salient Idea is that this simple push-and-pull dynamic governs the entire system.

The Aurora Connection

The location of the aurora is a direct visual indicator of this breathing. During a magnetic expansion (southward IMF), the boundaries of the magnetosphere are pushed out, and the auroral oval shifts towards the equator. This is why auroras are seen at lower latitudes during big storms. During a contraction (northward IMF), the oval shrinks back towards the pole. What about a substorm? The model explains the explosive phase as a rapid, partial *contraction* of the over-stretched magnetotail. This contraction violently flings particles back towards Earth, creating the bright, dynamic auroral surges on the poleward edge of the oval. A very strong, prolonged contraction can even bifurcate the magnetotail, creating the rare and beautiful transpolar arc known as a ‘theta aurora’.

A Peek Inside the Research

This isn’t just an idea; it’s backed by calculation and a proposal for a physical test. The author calculated the expected average thickness of the magnetopause boundary layer based on the observed 45-minute expansion and 8-hour contraction times of the aurora. The result, about 0.44 Earth radii, matches spacecraft observations perfectly. To further prove the concept, the paper outlines an upgrade to the famous 19th-century ‘terrella’ experiment. By adding a second large magnetic coil to simulate the IMF, a lab could physically demonstrate the expansion and contraction of the artificial auroral oval by simply flipping the polarity of the external ‘solar’ magnet. This brings a grand cosmic theory down to a testable, hands-on experiment.

The suggested 3D-spiral magnetic reconfiguration… avoids the topological crisis.

— E. P. Savov, on why this model is simpler

Key Takeaways

- Southward IMF acts like an attracting magnet, causing Earth's magnetosphere to expand and create storms.

- Northward IMF acts like a repelling magnet, causing the magnetosphere to contract and become quiet.

- A magnetic storm is just a very large, prolonged expansion of the magnetosphere.

- A substorm's explosive phase is a rapid, partial contraction that releases accumulated energy, creating auroral surges.

Sources & Further Reading

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: So does a substorm cause a magnetic storm?

A: According to this model, no. A magnetic storm is a large expansion of the magnetosphere caused by a long period of southward IMF. A substorm is a smaller expansion (growth phase) followed by a rapid, partial contraction (expansion phase) that releases energy, often weakening the larger storm.

Q: Why is this model better than the old ‘magnetic reconnection’ one?

A: The author argues it’s simpler and avoids certain theoretical problems, a principle known as Occam’s Razor. It explains confusing observations, like the storm-substorm timing, more intuitively by likening the magnetosphere’s behavior to simple magnetic attraction and repulsion.

Q: What happens when the solar wind pressure increases?

A: Higher solar wind pressure pushes on the magnetosphere, creating a longer, thicker magnetotail. This thicker tail is better at ‘catching’ the southward IMF, which then drives an even stronger expansion and a more intense magnetic storm.