Decoding a Planet's True Temperature

Summary

By the end of this article, you will understand why our first measurements of distant atmospheres are often misleading, and how scientists use computer models to correct for these illusions and reveal the true vertical structure of planets like Jupiter.

Quick Facts

- Surprise: The H3+ ion, a key atmospheric probe, was first discovered in Jupiter's aurora about 30 years ago.

- Salient Idea: Measuring a planet's atmosphere from afar is like looking at a multi-story building from above and trying to guess the temperature on each floor—you only get an average.

- Surprise: Standard observations of giant planets underestimate the amount of H3+ by 20% or more because of temperature gradients.

- Salient Idea: The same observed temperature changes on Uranus can be explained by the sun's angle (day vs. night), not necessarily by real atmospheric heating events.

- Surprise: Scientists combined 1995 data from the Galileo spacecraft with 2016 data from the Keck telescope to build a new, more accurate temperature profile of Jupiter.

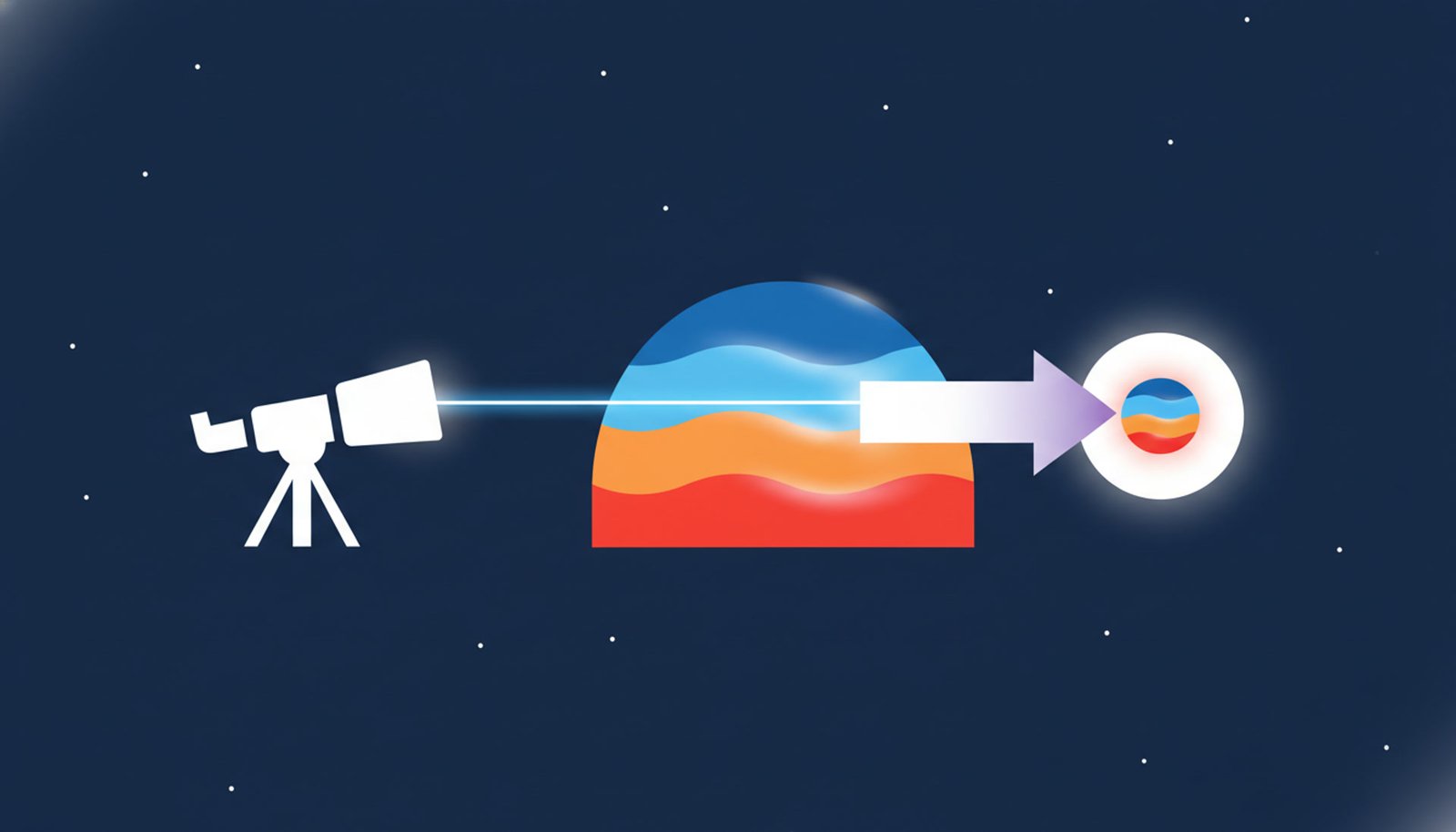

The Discovery: Seeing the Layers, Not the Lump

For decades, scientists have used the H3+ ion as a cosmic thermometer for giant planets. But they faced a persistent problem: their ground-based telescopes see the entire upper atmosphere at once, a ‘column-integrated’ view that averages everything together. This is like listening to an orchestra from outside the concert hall; you hear the sound, but you can’t pick out the individual instruments. The research team knew the atmosphere had layers with different temperatures and densities. The Story of this research is their solution: they built a ‘digital twin’ of the atmosphere in a computer. By creating a synthetic, layered atmosphere and simulating what a telescope would see, they could finally start to un-blend the signal. They found that the hotter, higher layers of H3+ dominate the light we see, systematically tricking us into measuring a higher temperature and a lower density than what’s really there.

The sheer diversity and uncertainty of conditions in planetary atmospheres prohibits this work from providing blanket quantitative correction factors; nonetheless, we illustrate a few simple ways in which the already formidable utility of H3+ observations… can be enhanced.

— L. Moore et al.

The Science Explained Simply

The key principle here is that the brightness of H3+ emissions increases exponentially with temperature. Imagine two equal groups of H3+ ions, one at 500K and one at 800K. The 800K group will glow far more intensely. This is NOT like looking at two rocks at different temperatures; this is about energized gas emitting light. When a telescope looks through an atmosphere with a cool layer below and a hot layer on top, the hot layer’s light completely overpowers the cool layer’s. The resulting measurement is therefore heavily weighted towards the hotter temperature. This ‘hot-weighting’ effect means the final number is not a true average. It’s a biased measurement that hides the cooler, lower-altitude gas, making us underestimate how much H3+ is there in total.

In a non-isothermal atmosphere, H3 column densities retrieved from such observations are found to represent a lower limit, reduced by 20% or more from the true atmospheric value.

— L. Moore et al.

The Aurora Connection

The H3+ ion was first discovered in Jupiter’s powerful aurora. Auroras are colossal curtains of light created when energetic particles, guided by the planet’s magnetic field, slam into the upper atmosphere. This process dumps enormous amounts of energy, heating the region intensely. H3+ plays a crucial role as a thermostat, radiating this excess energy back into space as infrared light and cooling the atmosphere. But how much cooling? To know that, we need to know the *true* temperature and density of H3+. This research provides the tools to get past the biased, column-integrated view and build a more accurate picture of the auroral energy budget. It helps us answer: how much energy is coming in from the solar wind and magnetosphere, and how efficiently is the planet getting rid of it? This is fundamental to understanding how planetary atmospheres respond to space weather.

A Peek Inside the Research

This wasn’t just theory; the scientists put their method to the test. Knowledge and Tools were key. First, they built a 1-D ionospheric model, a computer program that solves the physics and chemistry equations for a column of gas. They fed it data on solar radiation to simulate how the atmosphere gets ionized. For Jupiter, they went a step further, combining two very different datasets: a direct, in-situ measurement of electron density from the 1995 Galileo probe flyby, and a remote, column-integrated H3+ spectrum from the 2016 Keck Observatory. By forcing their model to reproduce *both* observations simultaneously, they were able to derive a self-consistent vertical temperature profile—a feat impossible with either dataset alone. This data fusion demonstrates a powerful new way to probe worlds we can’t visit directly.

Key Takeaways

- Column-integrated observations average out vertical details, leading to interpretation errors.

- Hotter, higher-altitude H3+ glows exponentially brighter, skewing temperature measurements high.

- Retrieved H3+ column densities are a lower limit, not the true value, in non-isothermal atmospheres.

- Forward-modelling (creating a 'digital twin') allows scientists to deconstruct the blended signal and infer the properties of individual atmospheric layers.

- Understanding the true temperature structure is vital for calculating energy balance, especially in auroral regions.

Sources & Further Reading

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is H3+ and why is it so important?

A: H3+ is a simple ion made of three hydrogen atoms and missing one electron. It’s abundant in the upper atmospheres of giant planets and glows brightly in infrared light, which our telescopes can see. This glow acts as a natural thermometer, allowing us to study the temperature and chemistry of these distant regions.

Q: Does this mean all our old measurements of Jupiter’s temperature are wrong?

A: They’re not ‘wrong’, but they are incomplete. They represent a biased average weighted towards the hottest parts of the upper atmosphere. This new work provides a method to correct for that bias and build a more detailed, layer-by-layer picture.

Q: Why can’t we just send more probes like Galileo to measure the layers directly?

A: Sending probes is incredibly expensive, complex, and provides only a single snapshot in one location at one time. Developing remote-sensing correction methods like this allows us to use ground-based telescopes to monitor the entire planet over many years, which is far more practical.

How to take northern lights video?

How to Take Video of the Northern Lights: A Complete Guide

Capturing a photograph of the Northern Lights is one thing, but filming their ethereal, dancing motion in real-time video is a challenge that offers an incredible reward. While photographers often use long exposures to create static images, videography requires a different approach to capture the fluid movement without it becoming a blurry mess.

Fortunately, modern mirrorless and DSLR cameras have become so powerful in low-light situations that capturing high-quality aurora video is more accessible than ever. This guide will walk you through the essential gear, core settings, and techniques you need to create breathtaking footage of the world’s greatest light show.

Essential Gear for Aurora Videography

Having the right equipment is the foundation of successful aurora videography. While you don’t need the most expensive gear on the market, a few key items are non-negotiable for dealing with the dark and cold conditions.

The Right Camera

The ideal camera for aurora video has two main features: full manual control in video mode and excellent high-ISO performance. Modern mirrorless cameras are often preferred because their electronic viewfinders can brighten the scene, making it easier to compose your shot in the dark. A full-frame sensor will generally perform better in low light and produce cleaner footage at high ISOs than a crop-sensor (APS-C) camera, but many modern crop-sensor cameras are still very capable. The ability to shoot in a ‘Log’ profile or RAW video format is a significant bonus, as it provides much greater flexibility for color grading in post-production.

Lenses: Wide and Fast

Your lens choice is arguably more important than the camera body. You need a ‘fast’ lens, which means it has a very wide maximum aperture. Look for a lens with an aperture of f/2.8 or wider (e.g., f/1.8, f/1.4). A wider aperture allows more light to hit the camera’s sensor, which is critical for video in near-total darkness. Secondly, you need a wide-angle lens, typically in the 14mm to 24mm range on a full-frame camera. This allows you to capture the vast scale of the aurora as it stretches across the sky and include some of the landscape for context and scale.

The Unshakeable Tripod

A sturdy tripod is absolutely essential. You will be using relatively slow shutter speeds, and any camera movement, even from the wind, will result in shaky, unusable footage. Don’t rely on a flimsy, lightweight travel tripod. Choose a robust model that can handle the weight of your camera and lens and remain stable in potentially windy conditions. A fluid video head is a great addition if you plan to introduce smooth panning or tilting movements, but a solid ball head will work perfectly for static shots.

Extra Batteries and Memory Cards

Cold weather is the enemy of battery life. The freezing temperatures common during aurora season can drain a fully charged battery in a fraction of the normal time. Always bring at least two or three spare batteries and keep them warm in an inside pocket of your jacket. Video files, especially 4K footage, are also enormous. Ensure you have several large, high-speed memory cards (e.g., 64GB or 128GB V60 or V90 rated cards) so you don’t run out of space during a spectacular display.

Core Camera Settings for Northern Lights Video

Balancing frame rate, shutter speed, aperture, and ISO is the key to technically sound aurora video. Unlike photography, these settings are more constrained and directly impact each other. Here’s a reliable starting point.

Frame Rate and Shutter Speed

For a cinematic look, set your frame rate to 24 frames per second (fps). To achieve natural-looking motion blur, videographers often follow the 180-degree shutter rule, which states your shutter speed should be double your frame rate. For 24fps, this would be 1/48s or 1/50s. This is a great starting point for a bright, fast-moving aurora. For a fainter, slower display, you may need to ‘break’ this rule and use a slower shutter speed like 1/30s or 1/25s to let in more light, but be aware this will create more motion blur.

Aperture (f-stop)

This is the easiest setting. You want to let in as much light as possible, so set your lens to its widest maximum aperture. If you have an f/1.8 lens, use f/1.8. If you have an f/2.8 lens, use f/2.8. This allows you to use the lowest possible ISO, which results in cleaner, less noisy footage. Some lenses are slightly soft when wide open, so you can consider stopping down by a tiny amount (e.g., from f/1.4 to f/1.6) for extra sharpness, but only if the aurora is bright enough to allow it.

ISO and White Balance

ISO controls the digital brightness of your video. With your aperture wide open and shutter speed set, ISO will be your main exposure control. Start with an ISO around 3200 or 6400 and adjust based on the aurora’s intensity. A bright, dynamic aurora might only need ISO 1600, while a faint one could require ISO 12800 or even higher. Be mindful that very high ISO values will introduce digital noise (grain). For color, do not use Auto White Balance. Set a manual Kelvin temperature, typically between 3200K and 4500K, to get a pleasing blue hour look for the night sky that renders the aurora’s green tones accurately.

Focusing in the Dark

Autofocus will not work in the dark. You must use manual focus. The best method is to find the brightest star or planet in the sky (or a very distant light on the horizon). Switch your camera to its live view mode and digitally magnify the view on that point of light. Carefully turn your lens’s focus ring until that light is as small and sharp as possible. Once you’ve nailed the focus, you can use a piece of gaffer tape to lock the focus ring in place so it doesn’t get bumped accidentally.

Quick Facts

- A camera with manual video controls and good high-ISO performance is essential.

- Use a wide-angle (14-24mm) lens with a fast aperture (f/2.8 or wider).

- A sturdy tripod is non-negotiable to prevent shaky footage.

- Start with these settings: 24fps, 1/50s shutter speed, widest aperture, and ISO 3200-6400.

- Always use manual focus; focus on a bright star using live view magnification.

- Cold drains batteries fast; bring multiple spares and keep them warm.

- Set a manual white balance (Kelvin 3200K-4500K) for accurate colors.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Can I film the Northern Lights with my phone? A: Yes, modern high-end smartphones (like recent iPhones or Google Pixels) can capture decent video of a bright aurora using their night modes. However, for the best quality, you will need a dedicated app that allows manual control over ISO and shutter speed, and you must use a tripod.

Q: What’s the difference between a timelapse and a real-time video? A: A timelapse is a series of still photos taken over a period and then stitched together to show movement. It’s great for very slow-moving auroras. A real-time video captures 24 (or more) frames every second, showing the fluid, true-speed dance of a fast-moving aurora, which a timelapse cannot replicate.

Q: How do I reduce noise in my aurora video? A: The best way to reduce noise is to capture the cleanest signal possible. Use a lens with a very wide aperture (like f/1.8 or f/1.4) to keep your ISO as low as possible. In post-production, you can use dedicated video noise-reduction software like Neat Video or the tools built into DaVinci Resolve or Adobe Premiere Pro.

Other Books

- B&H Photo Video – How to Shoot the Aurora Borealis in Video

- Sony Alpha Universe – See The Northern Lights In Real Time With These Pro Video Tips

- Lonely Speck – Ultimate Guide to Shooting the Milky Way (many principles apply)

Ganymede's Lopsided Sky

Summary

By the end of this article, you will understand how Jupiter’s largest moon, Ganymede, gets its thin atmosphere, and why its position in its orbit causes this atmosphere—and its auroras—to be strangely lopsided.

Quick Facts

- Surprise: Ganymede's atmosphere is primarily created by plasma from Jupiter crashing into its icy surface, a process called sputtering.

- Salient Idea: The oxygen atmosphere takes longer than one full orbit (~7 Earth days) to form, meaning its current state is a 'memory' of where it's been.

- Surprise: Jupiter's gravity, though weak at that distance, is strong enough to help shape Ganymede's long-lived oxygen exosphere.

- Surprise: The moon's 'afternoon' side is hotter, which enhances the sputtering process and contributes to a denser atmosphere at dusk.

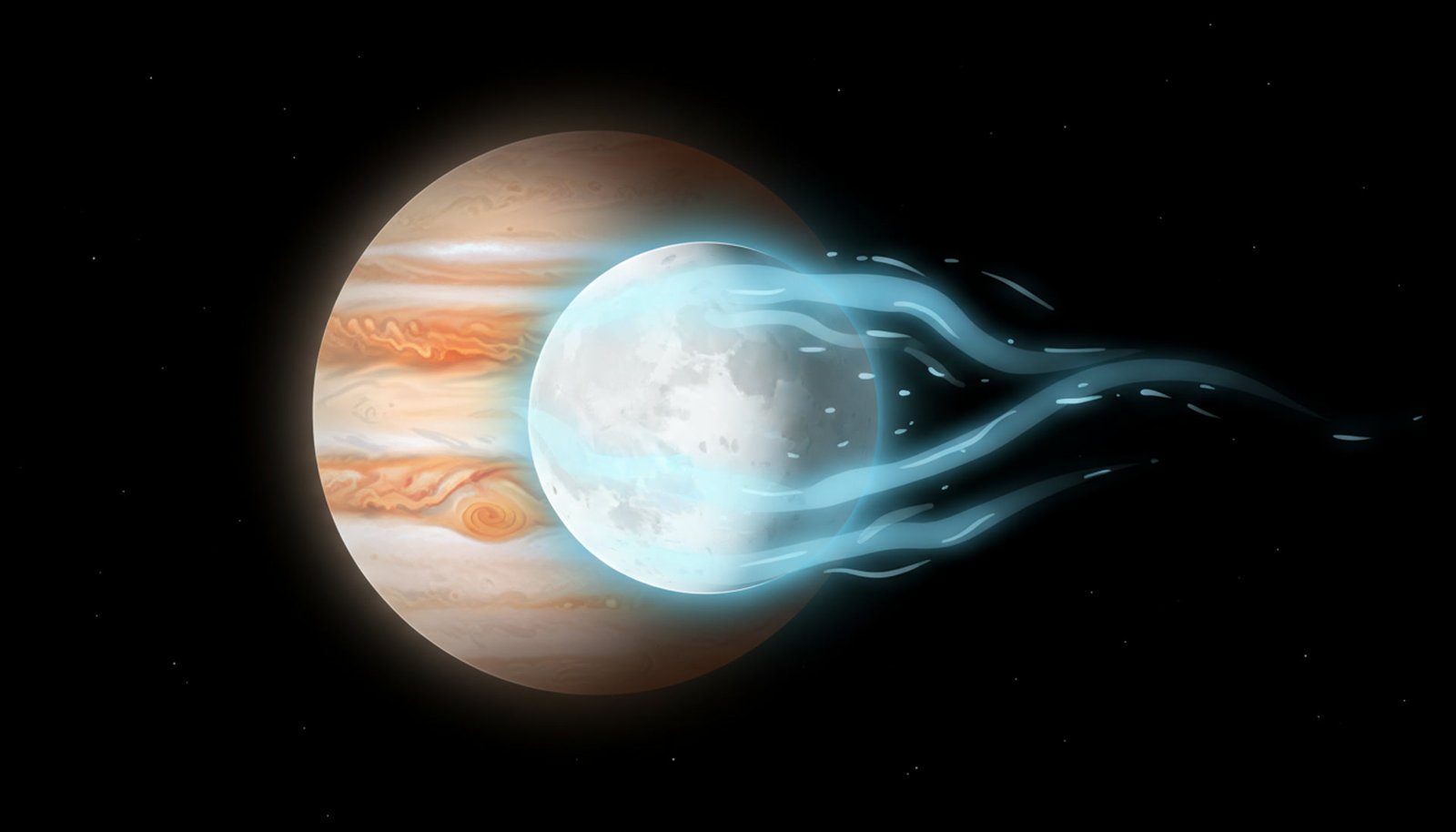

The Discovery: Modeling a Moon in Motion

For years, scientists struggled to explain why Ganymede’s auroras, observed by the Hubble Space Telescope, were often brighter on one side. Static models of its atmosphere just didn’t fit. The Story of this breakthrough lies in a new approach: simulating Ganymede not as a stationary object, but as a moon in constant motion. Using a powerful 3D computer model called the Exospheric Global Model (EGM), researchers tracked millions of virtual water and oxygen particles as they were sputtered off the ice. They simulated Ganymede’s full 7.2-day orbit around Jupiter. The model revealed a Surprise: the oxygen atmosphere builds up so slowly that it creates a lag, bunching up on the dusk side. This simulated atmospheric asymmetry perfectly matched the lopsided auroras. It was the first model to show the atmosphere ‘breathes’ with its orbit.

Original Paper: ‘On the orbital variability of Ganymede’s atmosphere’ by F. Leblanc et al.

The O2 exosphere should peak at the equator with a systematic maximum at the dusk equator terminator.

— F. Leblanc et al.

The Science Explained Simply

Ganymede’s atmosphere is NOT like Earth’s, which is a thick, stable blanket created from within. To understand it, we must build a fence around the concept. Ganymede’s atmosphere is an ‘exosphere’, a near-vacuum where molecules are constantly being created and lost. Its source is external: a relentless sandblasting by energetic particles trapped in Jupiter’s immense magnetic field. This process, called sputtering, kicks water ice molecules off the surface. Some of these molecules are broken down into oxygen (O2). Because this process is ongoing, the atmosphere is more of a temporary halo than a permanent feature. The key difference is its origin: it’s a direct result of space weather, not geology.

Ganymede’s atmosphere is produced by radiative interactions with its surface, sourced by the Sun and the Jovian plasma.

— Abstract from the paper

The Aurora Connection

Ganymede is the only moon in our solar system with its own magnetic field. This creates a small magnetic bubble that shields it from some of Jupiter’s plasma. However, at the poles, this shield is open, allowing Jovian plasma to funnel down and strike the surface. This impact does two things at once: it creates the oxygen atmosphere through sputtering, and it excites that very same oxygen, causing it to glow. These are Ganymede’s auroras. This research shows that the observed asymmetry in the auroras—brighter on the dusk side—is a direct map of the lopsided oxygen atmosphere below. The auroras aren’t just pretty lights; they are a visual confirmation of the dynamic, orbiting ‘weather’ patterns in Ganymede’s exosphere.

A Peek Inside the Research

This discovery wasn’t made with a telescope alone; it required immense computational power. The team’s Knowledge and Tools centered on a 3D Monte Carlo simulation. This program acts like a virtual Ganymede, tracking the fate of millions of individual ‘test-particles’ representing different molecules. It calculated their ejection speed from sputtering, their trajectory under the pull of both Ganymede’s and Jupiter’s gravity, and even the tiny chance they would collide with each other. Simulating just 4.5 orbits took two weeks on 64 CPUs. This painstaking digital reconstruction was the only way to reveal the slow, lagging formation of the oxygen exosphere that happens over days—a process too subtle to capture in a single snapshot.

Key Takeaways

- A moon's atmosphere can be dynamic, changing its shape and density based on its orbit around a planet.

- Ganymede's personal magnetic field channels Jovian plasma to its poles, making them the primary source of its atmosphere.

- The slow-moving, heavy oxygen molecules are influenced by non-inertial forces, pushing them toward the equator.

- Observing a moon's aurora can reveal hidden asymmetries in its tenuous atmosphere.

Sources & Further Reading

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why is the atmosphere thicker on the ‘dusk’ side?

A: It’s a combination of factors. The surface is warmest in its local ‘afternoon’ (the dusk side), which makes the sputtering process more efficient. Furthermore, the heavy oxygen molecules take a very long time to spread out, so they tend to cluster in the region where they are most actively produced.

Q: Does Ganymede have weather?

A: Not like Earth. It’s far too thin for clouds or wind. However, its atmospheric density changes dramatically depending on where it is in its orbit and the time of day, which is a unique form of ‘space weather’.

Q: Why is Ganymede’s magnetic field so important for its atmosphere?

A: Ganymede’s magnetic field acts like a funnel. It guides the energetic plasma from Jupiter down to the polar regions. This focuses the sputtering process at the poles, making them the primary ‘source regions’ for the entire atmosphere.

How were the northern lights visible last night?

Why Are the Northern Lights Sometimes Visible Farther South?

Seeing the Northern Lights dance across the sky is a breathtaking experience, but it’s even more shocking and memorable when they appear in a location far from the Arctic Circle. Events like these, where the aurora is visible across much of Europe and the United States, are not random occurrences. They are the direct result of powerful eruptions on the surface of the Sun.

Understanding why this happens involves looking at the Sun’s activity and how it interacts with our planet’s protective magnetic shield. A stronger-than-usual solar event can supercharge this interaction, pushing the beautiful light show to millions of new viewers.

The Sun's Role: From Calm to Stormy

The visibility of the aurora is directly tied to the Sun’s behavior. Under normal conditions, the show is confined to the polar regions. But when the Sun unleashes a major storm, the rules change.

Normal Conditions: The Auroral Oval

On a typical night, the Northern Lights occur within a ring around the North Magnetic Pole known as the auroral oval. This ring usually covers northern Scandinavia, Siberia, Alaska, and northern Canada. The strength of the aurora on any given night is measured by the Kp-index, a scale from 0 to 9. Normal activity is usually in the Kp-1 to Kp-3 range, keeping the lights confined to these high-latitude regions. This ‘normal’ activity is caused by the steady stream of particles called the solar wind. Think of it as a constant, gentle breeze that powers a predictable light show in the far north.

The Game Changer: Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs)

A widespread aurora display is caused by something much more powerful than the normal solar wind. A Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) is a massive eruption of plasma and magnetic field from the Sun’s corona. If the solar wind is a breeze, a CME is a hurricane. It hurls billions of tons of solar particles into space at immense speeds, sometimes over several million miles per hour. If a CME is aimed at Earth, it can trigger a geomagnetic storm, which is the event responsible for pushing the aurora south. These events are more common during the peak of the Sun’s 11-year activity cycle, known as the solar maximum.

Impact on Earth’s Magnetic Field

When a powerful CME arrives at Earth, it slams into our planet’s protective magnetic shield, the magnetosphere. This collision compresses the magnetic field on the day side of Earth and elongates it into a long tail on the night side. This process transfers a huge amount of energy into the magnetosphere. The magnetic field lines snap back like a stretched rubber band, accelerating charged particles down into the atmosphere at much lower latitudes than usual. This is the key mechanism that expands the auroral oval, allowing people in places like the northern United States or central Europe to witness the spectacle.

The Result: An Expanded Light Show on Earth

The aftermath of a CME’s arrival is a supercharged and geographically expanded aurora, often with more intense colors and faster movements.

The Kp-index and Your Location

The Kp-index becomes crucial for predicting visibility during a storm. While a Kp-3 might mean lights in northern Norway, a Kp-5 indicates a moderate storm, potentially bringing the aurora to the northern US border and Scotland. A strong storm, rated Kp-7, can push the aurora view line down to states like Illinois and Oregon in the US, and Germany or Poland in Europe. A major, rare storm at Kp-9 could make the aurora visible as far south as Florida and Texas. By checking real-time space weather forecasts for the predicted Kp-index, you can know if you have a chance to see the lights from your backyard.

Seeing Red: The Colors of a Solar Storm

While green is the most common aurora color, strong geomagnetic storms often produce vibrant red auroras. This happens because the incoming solar particles are so energetic that they can reach and excite oxygen atoms at very high altitudes (above 150 miles or 240 km). At these heights, excited oxygen emits a crimson glow. Seeing red in the aurora is often a sign of a particularly intense and widespread storm. You might also see pinks, which are a mix of red light from above and green light from below, or deep purples from collisions with nitrogen molecules.

Quick Facts

- Powerful solar storms, especially Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs), are the primary cause of auroras visible at mid-latitudes.

- These storms expand the ‘auroral oval’, the ring where auroras typically occur, southward.

- The Kp-index is a scale from 0-9 that measures geomagnetic activity and helps predict how far south the aurora will be visible.

- A Kp-index of 7 or higher can bring the Northern Lights to the northern US and central Europe.

- Strong storms often produce rare, high-altitude red auroras in addition to the common green.

- Such events are more frequent during the ‘solar maximum’, the peak of the Sun’s 11-year cycle.

- To see the lights, you need a strong storm, clear skies, and a location away from city light pollution.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: How often do these strong solar storms happen? A: The frequency of strong solar storms follows the Sun’s 11-year solar cycle. During the peak of the cycle, called the solar maximum, major storms can occur several times a year. During the solar minimum, they are much rarer.

Q: Can I predict when the aurora will be visible in my area? A: Yes, you can follow space weather forecasts from sources like NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center. They issue watches and warnings for geomagnetic storms and provide Kp-index forecasts, which are the best tools for predicting visibility.

Q: Are the geomagnetic storms that cause these auroras dangerous? A: The aurora itself is completely harmless to people on the ground. However, the underlying geomagnetic storm can pose risks to technology, potentially disrupting power grids, satellite operations, and GPS communications.

Other Books

- NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center – Official Forecasts

- SpaceWeatherLive – Real-time Auroral and Solar Data

- NASA’s Explanation of the Solar Cycle

SMILE: X-Raying Earth's Invisible Shield

Summary

By the end of this article, you will understand how scientists are using X-rays—usually considered background noise—to create the first-ever movies of Earth’s invisible magnetic shield as it battles the solar wind.

Quick Facts

- Surprise: The mission's key signal is a type of X-ray that astronomers usually treat as unwanted background noise.

- Salient Idea: For the first time, we'll get a 'movie' of the magnetosphere's boundary instead of single-point measurements.

- Surprise: It's the first-ever joint mission from start to finish between the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS).

- Salient Idea: SMILE will spend over 80% of its 51-hour orbit continuously watching the Earth-Sun interaction.

- Surprise: Its X-ray camera uses special 'lobster-eye' optics to get a super wide-angle view of the sky.

The Discovery: Turning Noise Into a Signal

For years, astronomers studying distant galaxies were annoyed by a faint, variable X-ray glow that contaminated their images. This ‘noise’ was eventually traced back to our own solar system. It happens when charged particles from the solar wind smash into the edge of Earth’s atmosphere (the exosphere). This process, called Solar Wind Charge Exchange (SWCX), creates a faint X-ray emission. The Story of SMILE is a brilliant pivot: what if, instead of trying to remove this ‘noise’, we built a mission specifically to capture it? Scientists realized these X-rays perfectly outline the invisible boundaries of our magnetosphere. SMILE was born from this idea to turn a problem into a revolutionary solution for seeing our planet’s defenses in action.

The SMILE mission (Branduardi-Raymont & Wang)

The international space plasma and planetary communities are looking forward to the step change that SMILE will provide by making visible our invisible terrestrial magnetosphere.

— G. Branduardi-Raymont & C. Wang, SMILE Mission Scientists

The Science Explained Simply

The X-rays SMILE sees are NOT coming from the Sun. Instead, they are made right here at Earth. Here’s how: the solar wind is a stream of highly charged ions. Earth is surrounded by a vast, thin cloud of neutral atoms called the exosphere. When a solar wind ion gets close to a neutral atom, it steals an electron. The ion is now in a highly excited, unstable state. To become stable, it releases energy by spitting out a photon of light—specifically, a soft X-ray. This is Building a Fence: it’s not a reflection or a solar emission. It is a local light show powered by a cosmic collision. Where the solar wind is densest—at the magnetopause and cusps—the X-ray glow is brightest, giving SMILE a perfect target to film.

SMILE combines this with simultaneous UV imaging of the northern aurora and in-situ plasma and magnetic field measurements.

— Abstract from the research paper

The Aurora Connection

The aurora is the beautiful end-product of a long chain of events that starts with the solar wind. SMILE is designed to see the entire chain. Its Soft X-ray Imager (SXI) will watch the cause: the large-scale boundary where the solar wind slams into Earth’s magnetic shield. At the very same time, its UltraViolet Imager (UVI) will watch the effect: the glowing oval of the northern aurora, where energized particles rain down into our atmosphere. By having both cameras running simultaneously, scientists can directly answer questions like: ‘When the magnetic shield gets compressed by a solar storm, how quickly and in what way does the aurora respond?’ It forges an undeniable link between the macro-scale physics of deep space and the beautiful light shows above our poles.

A Peek Inside the Research

Before building a multi-million dollar spacecraft, you have to be sure it will work. A huge part of the work for SMILE involved Knowledge and Tools in the form of computer simulations. Researchers used Magneto-Hydro-Dynamic (MHD) models to predict what the magnetosphere would look like under different solar wind conditions. Then, they calculated the expected X-ray glow from these models. Finally, they fed these virtual X-ray maps into a simulator for the SXI instrument, including all its limitations and sources of background noise. This painstaking process allowed them to prove that SMILE could, in fact, accurately locate the magnetopause with a precision of 0.5 Earth radii and a time resolution of 5 minutes, meeting its core science goals before a single piece of hardware was built.

Key Takeaways

- Solar Wind Charge Exchange (SWCX) is a natural process that generates X-rays at the boundary of our magnetosphere.

- Imaging this X-ray light allows us to see the location, shape, and motion of the invisible magnetopause.

- By watching the aurora in UV light at the same time, SMILE directly links global space weather drivers to their effects in our atmosphere.

- This global view is essential for testing and improving the computer models that predict space weather.

- SMILE turns a nuisance into a powerful diagnostic tool, a classic story of scientific innovation.

Sources & Further Reading

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why can’t we just see the magnetic field directly?

A: Magnetic fields themselves are completely invisible. We can only detect their effects. SMILE uses the X-rays as a tracer, like adding dye to water to see the flow. The X-rays light up the boundary where the solar wind plasma interacts with the field, making the invisible visible.

Q: What is ‘space weather’ and why does it matter?

A: Space weather refers to the changing conditions in space driven by the Sun, like solar flares and Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs). These events can disrupt satellites, damage power grids on Earth, and pose a radiation risk to astronauts. SMILE will help us understand and better forecast these events.

Q: Why is the orbit so important?

A: SMILE will be in a huge, highly elliptical orbit that takes it far above Earth’s north pole. From this high vantage point, it can stare down at the dayside magnetosphere for over 40 hours at a time, capturing long, uninterrupted movies of the solar wind interaction without the Earth getting in the way.

How long do northern lights usually last?

How Long Do the Northern Lights Usually Last?

One of the most common questions from aspiring aurora chasers is about timing: ‘If I see them, how long will they stick around?’ The answer is as dynamic as the lights themselves. The Northern Lights are not a static phenomenon; they are a live performance put on by the Sun and Earth’s atmosphere, and the length of the show can be unpredictable.

While many displays are fleeting, lasting just long enough for a few breathtaking photos, others can fill the sky with dancing light from dusk until dawn. Understanding the factors that influence an aurora’s duration can help you manage expectations and maximize your chances of witnessing a truly unforgettable spectacle.

Understanding Aurora Duration: From Minutes to Hours

The length of an aurora display is directly tied to the behavior of the solar wind hitting Earth. Think of it like a fire: a small, quick gust of wind might cause a brief flare-up, while a steady, strong wind can keep the fire roaring for hours.

The Typical Display: 15-30 Minutes

For most observers, a typical, memorable aurora display is part of an event called a geomagnetic substorm. This is a relatively short, intense burst of energy released into the atmosphere. The display often starts as a simple, faint arc across the sky. As the substorm peaks, this arc can suddenly brighten and explode into dynamic, fast-moving curtains and rays of light. This peak activity, the most ‘active’ and photogenic part of the show, usually lasts for 15 to 30 minutes. Afterward, the lights may fade back into a quiet arc or disappear entirely as that specific injection of energy subsides.

The Brief Flicker: A Few Minutes

Sometimes, the conditions for an aurora are only marginally met. The solar wind might be weak, or its magnetic field orientation might be unfavorable for energy transfer. In these cases, you might only witness a brief flicker of auroral activity lasting just a few minutes. This can manifest as a faint, greyish-green glow on the horizon that is barely visible to the naked eye, or a short-lived patch of light that quickly dissipates. These minor events are very common but are often missed by casual observers. They represent the constant, low-level interaction between the solar wind and our planet’s magnetic shield.

The All-Night Spectacle: Several Hours

The holy grail for aurora hunters is the all-night display. These long-lasting events are powered by major solar events, most notably a Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) or a high-speed solar wind stream. When one of these hits Earth, it provides a powerful, continuous flow of energy into the magnetosphere for many hours. This results in a major geomagnetic storm. During such a storm, the aurora can remain active and dynamic for the entire night, going through multiple cycles of brightening, dancing, and fading, only to roar back to life again. These are the events that bring the aurora to lower latitudes and create the most awe-inspiring memories.

Key Factors Influencing Aurora Longevity

The duration of the aurora isn’t random. It’s governed by specific conditions in space weather, primarily the characteristics of the solar wind arriving at Earth.

Solar Wind and the ‘Southward Bz’

The single most important factor for a strong, long-lasting aurora is the orientation of the Interplanetary Magnetic Field (IMF), which is carried by the solar wind. Specifically, its north-south component, known as ‘Bz’. When the Bz is oriented southward (negative), it effectively ‘opens a door’ in Earth’s magnetosphere, allowing vast amounts of energy and particles to flow in. A strong and sustained southward Bz is the primary ingredient for a geomagnetic storm that can fuel the aurora for hours. If the Bz is northward (positive), the ‘door’ is mostly closed, and any auroral activity will be weak and short-lived.

The Role of Earth’s Rotation

From a fixed location on the ground, the duration of a display can also be influenced by Earth’s rotation. The aurora occurs in a giant ring around the magnetic pole called the auroral oval. This oval is generally fixed in place relative to the Sun. As the Earth rotates underneath it, your location on the ground moves into, through, and out of the most active part of this oval. The peak viewing time is typically around magnetic midnight (roughly 10 PM to 2 AM), when your location is under the most active, night-side portion of the oval. This is why a display might seem to fade late at night, simply because your viewing spot has rotated out of the prime zone.

The Dynamic Nature of a Display

Even during a long-lasting storm, the aurora is rarely constant. It’s important to understand that the lights ‘breathe’—they have their own rhythm of brightening and fading.

Ebbs and Flows

An aurora display is not a steady light. It is constantly changing in brightness, shape, and intensity. During a multi-hour event, it’s common to experience periods of intense, fast-moving coronas and curtains, followed by lulls where the light softens to a diffuse glow or a simple arc. Patience is key. Many novice aurora watchers make the mistake of leaving during a quiet period, only to miss a spectacular outburst an hour later. If a strong storm is forecast, it’s worth waiting through the lulls, as the show is likely not over. These ebbs and flows are the natural cycle of energy being stored and released in Earth’s magnetotail.

Quick Facts

- A typical aurora display, or ‘substorm’, lasts for 15-30 minutes.

- Major geomagnetic storms caused by CMEs can produce auroras that last for many hours.

- The duration is primarily controlled by the strength and consistency of the solar wind.

- A sustained southward Bz component of the Interplanetary Magnetic Field is crucial for long-lasting displays.

- The best viewing time is often around magnetic midnight (10 PM – 2 AM local time).

- Aurora displays are dynamic; they naturally brighten and fade in cycles.

- Even on a quiet night, you might see a brief flicker of auroral light lasting only a few minutes.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Do the Northern Lights happen every night? A: Yes, the aurora is almost always present somewhere within the auroral oval. However, its visibility from the ground depends on your location, clear skies, darkness, and the current level of geomagnetic activity.

Q: Can an aurora display stop and then start again? A: Absolutely. It is very common for a display to fade away for 30 minutes to an hour, only to return with another brilliant burst of activity. This is part of the natural cycle of substorms during a period of heightened activity.

Q: If the forecast is strong, am I guaranteed to see them all night? A: Not necessarily. A strong forecast increases the probability of a long-lasting event, but the timing and intensity can still be unpredictable. The solar wind is turbulent, and conditions can change, causing the aurora to fluctuate in strength throughout the night.

Other Books

- NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center – Aurora Dashboard

- University of Alaska Fairbanks – What is a Substorm?

- Space.com – Aurora Borealis: What Causes the Northern Lights & Where to See Them

Stars That 'Sing' for Their Planets

Summary

By the end of this article, you will understand how a planet can create a radio signal on its host star, and how scientists use this ‘auroral footprint’ to hunt for exoplanets and their crucial magnetic fields.

Quick Facts

- Surprise: We're not listening to the planet, but to the star's radio 'shout' caused by the planet.

- The TRAPPIST-1 system of seven planets is a prime target for this type of radio detection.

- This phenomenon is a scaled-up version of the interaction between Jupiter and its volcanic moon, Io.

- A planet's magnetic field is a key ingredient for protecting a potential atmosphere and enabling life.

- The radio signal would pulse in time with the planet's orbit, like a cosmic lighthouse.

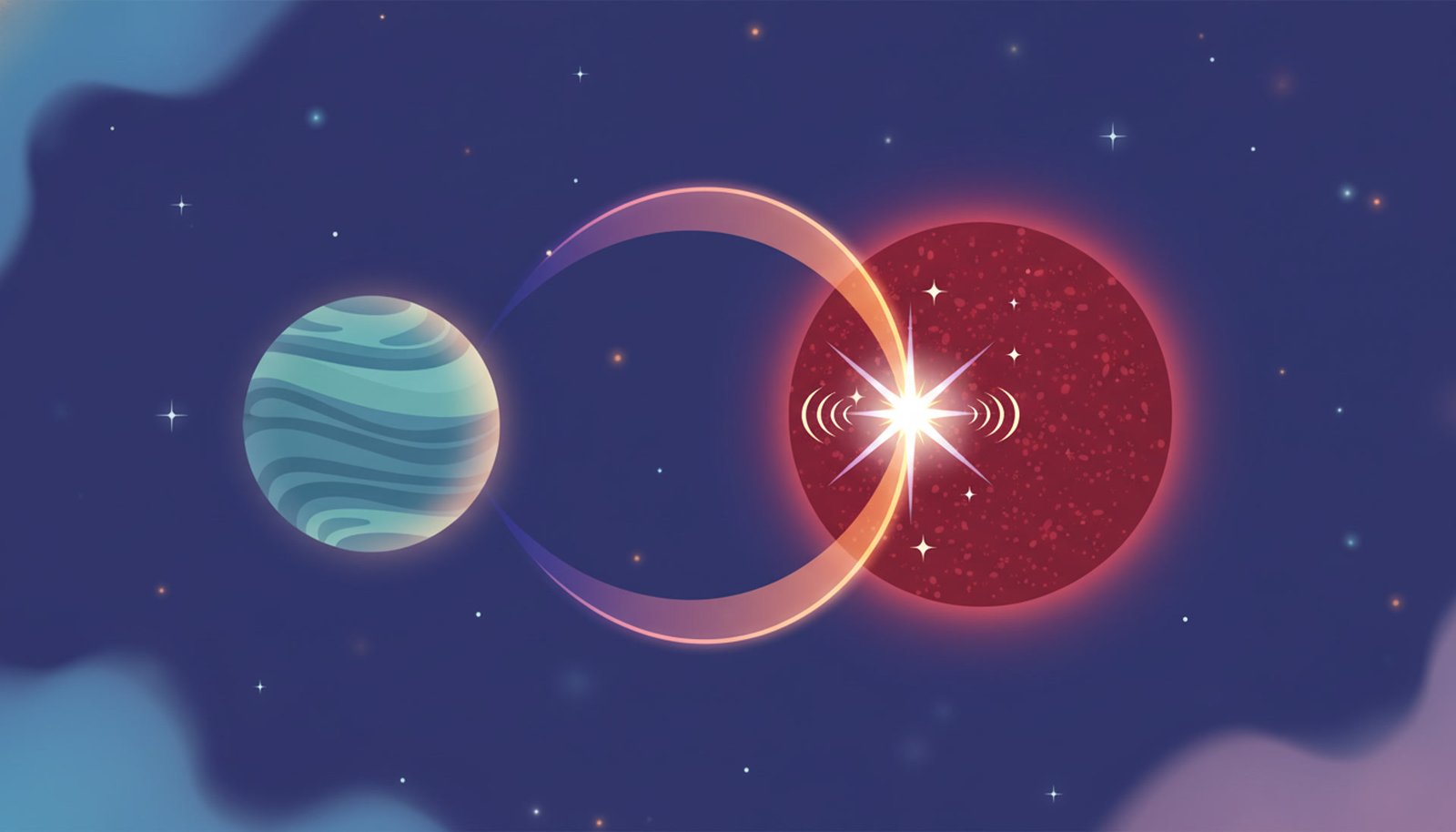

The Discovery: Tuning In to a Star's Echo

How do you find a planet that’s too small and quiet to detect directly with a radio telescope? A team at the University of Leicester came up with a clever solution. Their Story is one of inspiration. They looked at our own solar system, specifically at Jupiter and its moon Io. Io’s movement through Jupiter’s magnetic field creates a powerful electrical circuit, leaving a glowing auroral ‘footprint’ in Jupiter’s atmosphere. The researchers theorized that exoplanets orbiting close to M-dwarf stars could do the same thing on a much grander scale. They built a model to calculate the energy transferred from the planet to the star and predicted the strength of the resulting radio signal. Their work identifies 11 specific systems that might be ‘singing’ right now, waiting to be heard.

Original Paper: ‘Exoplanet-Induced Radio Emission from M-Dwarfs’ by Turnpenney et al.

A region of emission analogous to the Io footprint observed in Jupiter’s aurora is produced.

— Sam Turnpenney et al.

The Science Explained Simply

Imagine a river: the stellar wind flowing from the star. Now, put a rock in it: the exoplanet. Normally, the wake flows downstream. But if the river flows slower than the speed of ‘sound’ in that medium (the Alfvén speed), something amazing happens: the disturbance can travel upstream. This is a sub-Alfvénic interaction. This is NOT the planet beaming radio signals into space. Instead, the planet’s presence creates a disturbance in the star’s magnetic field, forming two ‘Alfvén wings’ that act like cosmic wires. These wires carry energy back to the star’s surface. When that energy arrives, it accelerates electrons in the star’s atmosphere, which then release that energy as a focused beam of radio waves.

Energy can be transported upstream of the flow along Alfvén wings.

— NorthernLightsIceland.com Team

The Aurora Connection

The phenomenon described in the paper is a direct cousin to the auroras we see on Earth and Jupiter. The ‘Io footprint’ on Jupiter is a persistent auroral spot caused by the magnetic connection to its moon. This research predicts a similar ‘exoplanet footprint’ on M-dwarf stars. For a planet to create this effect, it needs either a protective magnetic field or a thick atmosphere to act as an obstacle. Therefore, detecting this radio signal is a powerful clue that the planet has a magnetic shield. That shield is the single most important factor in protecting an atmosphere from being stripped away by the stellar wind—a prerequisite for life as we know it and for any planet to host its own auroras.

A Peek Inside the Research

This wasn’t just a guess; it was a feat of calculation. The researchers used a model of stellar wind (the Parker spiral) to determine the plasma conditions around the star. They then calculated the ‘Poynting flux’—the amount of energy carried along the Alfvén wings. Finally, they estimated how much of that energy would be converted into radio waves by the electron-cyclotron maser instability (ECMI). To make their predictions, they had to estimate planetary properties, like magnetic field strength, using scaling laws. They ran these calculations for 85 known exoplanets orbiting M-dwarfs to create a priority list for radio telescopes like the VLA and the future SKA, turning a theoretical idea into a concrete observation plan.

Key Takeaways

- Planets moving through stellar wind can send energy 'upstream' to their star.

- This energy transfer happens along magnetic 'Alfvén wings'.

- The energy hitting the star's atmosphere can trigger a powerful radio burst via the ECMI mechanism.

- This method allows us to potentially detect Earth-sized planets and measure their magnetic fields.

- M-dwarf stars are ideal targets because their habitable zones are very close, strengthening the interaction.

Sources & Further Reading

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: So, are we listening to aliens?

A: No, we are not listening for intelligent communication. We are listening for a natural radio emission caused by the physical interaction between a planet and its star, similar to how Jupiter’s moons create auroras.

Q: Why can’t we just listen to the planet’s own radio signal?

A: For Earth-sized planets, the radio signals they might produce are at very low frequencies. These signals get trapped by the planet’s own ionosphere and can’t escape into space for us to detect. This indirect method bypasses that problem by having the much more powerful star do the broadcasting.

Q: Does this mean these planets have life?

A: Not directly, but it’s a huge step. A strong magnetic field is essential for protecting a planet’s atmosphere, which is a key requirement for habitability. Finding a magnetic field would be a very promising sign.

How to see northern lights in UK?

How to See the Northern Lights in the UK: A Complete Guide

The magical dance of the Aurora Borealis isn’t reserved just for Arctic destinations like Iceland or Norway. Under the right conditions, this celestial light show can be witnessed from the UK, offering a breathtaking experience closer to home. However, seeing them here requires a perfect alignment of space weather and Earth weather.

This guide will walk you through everything you need to know, from the science that brings the lights south to the best locations and tools to use, transforming you into a skilled UK aurora hunter.

The Three Key Ingredients for a UK Sighting

Spotting the aurora in the UK depends on three critical factors coming together at the same time. If any one of these is missing, your chances drop significantly.

Ingredient 1: Strong Solar Activity

The Northern Lights are caused by particles from the sun hitting our atmosphere. For the aurora to be visible as far south as the UK, we need a particularly strong stream of these particles, usually from a Coronal Mass Ejection (CME). Scientists measure this activity using the Kp-index, a scale from 0 to 9. For a faint glow to be possible in Scotland, you typically need a Kp-index of 5 or higher. For sightings in Northern England or Wales, you’ll often need a Kp of 6 or 7. Following real-time aurora alerts from services like AuroraWatch UK is crucial, as they will tell you when solar activity is high enough.

Ingredient 2: A Clear, Dark Sky

This is the most common obstacle for UK aurora hunters: the weather. You need a cloud-free sky to see the lights. It’s essential to check the local weather forecast, paying close attention to cloud cover. Equally important is escaping light pollution. City and town lights create a ‘sky glow’ that will wash out the faint aurora. You must travel to a rural area, ideally a designated Dark Sky Park, and give your eyes at least 15-20 minutes to fully adjust to the darkness. Face north, away from any direct light sources, and find a spot with an unobstructed view of the northern horizon.

Ingredient 3: The Right Time of Year and Night

While it’s possible to see the aurora anytime there are dark nights, your chances are statistically highest during the months around the spring and autumn equinoxes (March/April and September/October). This is due to a phenomenon known as the ‘Russell-McPherron effect’, where Earth’s tilt is optimally aligned to receive solar wind. The long, dark nights of winter are also good, but summer is impossible due to the lack of true darkness. The best time of night is typically between 10 PM and 2 AM, when the sky is at its darkest.

Where to Go: Best UK Locations for Aurora Hunting

Location is everything. The further north you go, the better your chances are of seeing the aurora over the horizon.

Scotland: The UK’s Aurora Hotspot

Scotland is, without a doubt, the premier destination for seeing the Northern Lights in the UK. Its high latitude means the auroral oval is closer. The Shetland and Orkney Islands offer the very best odds. On the mainland, the northern coast, including the NC500 route, Caithness, and Sutherland, provides fantastic opportunities. The Cairngorms National Park, being a dark sky park, is another excellent choice. Even further south, places like Galloway Forest Park (another dark sky park) and the coasts of Fife and Aberdeenshire can yield sightings during strong storms.

Northern England: Your Next Best Bet

During a strong geomagnetic storm (Kp 6+), the aurora can be seen from the northern counties of England. The Northumberland International Dark Sky Park is arguably the best place in England, offering pristine dark skies and a clear northern horizon over the sea. The Lake District National Park, particularly around its northern lakes like Derwentwater, is another prime spot. The higher elevations of the Yorkshire Dales and North York Moors can also provide the necessary darkness and vantage points to catch a rare display.

Wales and Northern Ireland: Possible but Rare

Seeing the aurora from Wales and Northern Ireland is a true treat, requiring a very powerful storm (Kp 7+). In Wales, your best bet is to head to the darkest areas with a clear view north, such as the Snowdonia National Park or the coast of Anglesey. In Northern Ireland, the Antrim Coast, particularly around Dunluce Castle or the Giant’s Causeway, offers a stunning and dark foreground for potential displays. Patience and a significant space weather event are key for a successful hunt in these regions.

Quick Facts

- Scotland offers the best chance of seeing the aurora in the UK due to its higher latitude.

- A strong geomagnetic storm, measured by a Kp-index of 5 or higher, is required.

- The best months are around the equinoxes: March, April, September, and October.

- You must be in a location with minimal light pollution and no cloud cover.

- Look towards the northern horizon, typically between 10 PM and 2 AM.

- To the naked eye in the UK, the aurora often appears as a faint white or grey arc, not vivid dancing curtains.

- Use apps like AuroraWatch UK for real-time alerts on when to look up.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Can I see the Northern Lights from London or the South of England? A: It is exceptionally rare. This would require a once-in-a-decade geomagnetic storm (Kp-index 8 or 9). While it has happened, it is not something you can realistically plan for.

Q: What does the aurora look like to the naked eye in the UK? A: Often, it doesn’t look like the vibrant green photos. It usually starts as a faint, greyish-white glow or arc low on the northern horizon, easily mistaken for a cloud. A long-exposure photo with a camera will reveal the green and purple colours that your eyes can’t pick up.

Q: Do I need a special camera to see the colours? A: A modern smartphone with a ‘night mode’ can often capture the colours surprisingly well. For the best results, a DSLR or mirrorless camera on a tripod with a long exposure (5-20 seconds) is ideal for capturing the vivid details and colours of the aurora.

Other Books

- AuroraWatch UK – Real-time alerts from Lancaster University

- Met Office UK – Space Weather Forecast

- Northumberland International Dark Sky Park

How long does northern lights strain take to grow?

How Long Do the Northern Lights Last?

When searching for information on the ‘Northern Lights’, it’s common to encounter two very different topics: the breathtaking natural light show in the sky (Aurora Borealis) and a well-known cannabis strain. This article focuses exclusively on the natural celestial phenomenon.

One of the most common questions for aurora chasers is, ‘Once they appear, how long will they stick around?’ The answer is not simple, as the duration of an aurora display is as variable as its shape and color. Understanding the forces that drive the aurora helps explain why some shows are brief flashes while others are epic, all-night events.

Understanding Aurora Duration

The length of an aurora display is directly tied to the space weather conditions causing it. Think of it like a celestial faucet: the longer the solar wind ‘faucet’ is turned on and pointed at Earth, the longer the light show will last.

Typical Display Timespan

For a casual observer, a typical auroral ‘substorm’ or burst of activity often lasts between 15 and 40 minutes. During this time, the lights can go from a faint, static arc to a vibrant, dancing curtain of light that fills the sky. It’s common for the aurora to appear, put on a spectacular show, and then fade away, sometimes returning later in the night if conditions persist. Many aurora hunters pack their patience, as a quiet sky can erupt with light with little warning. It’s not a continuous event like a sunset; it’s a series of dynamic, often unpredictable, bursts of light.

Factors Influencing Duration

The primary factor determining how long the Northern Lights last is the solar wind streaming from the Sun. Specifically, the orientation of the interplanetary magnetic field (IMF) carried by the solar wind is crucial. When the IMF is oriented southward (a negative ‘Bz’ value), it efficiently connects with Earth’s magnetosphere, allowing energy to pour in. As long as this southward Bz condition persists, the aurora can continue. A strong, long-lasting stream of solar wind, such as from a coronal hole high-speed stream or a Coronal Mass Ejection (CME), can create intense auroras that last for many hours or even across multiple nights.

All-Night Auroras: Geomagnetic Storms

The most spectacular, long-lasting displays occur during geomagnetic storms. These are major disturbances of Earth’s magnetosphere caused by a powerful CME hitting our planet. During a strong storm (e.g., G3 or higher on the NOAA scale), the aurora can be visible for the entire night, from dusk until dawn. The display will ebb and flow in intensity, with multiple powerful substorms creating waves of activity. These are the events that allow the aurora to be seen at much lower latitudes than usual and provide the hours-long light shows that photographers and sky-watchers dream of.

Clarifying the 'Northern Lights' Name

It’s important to clarify that this website discusses the astronomical phenomenon. The term ‘Northern Lights’ has been adopted by others, which can cause confusion.

The Natural Wonder: Aurora Borealis

The Aurora Borealis, or Northern Lights, is a natural light display in Earth’s sky, predominantly seen in high-latitude regions. It is caused by collisions between energetic particles (electrons and protons) from the sun, carried by the solar wind, and gas particles in our own upper atmosphere. These collisions excite the gas atoms, causing them to emit light of different colors, most commonly green. This is a phenomenon of physics and astronomy, studied by agencies like NASA and NOAA. It is a beautiful, harmless, and awe-inspiring spectacle.

A Note on the Cannabis Strain

There is also a famous strain of cannabis named ‘Northern Lights’. It was named for its desirable characteristics, but it has no physical or scientific connection to the actual Aurora Borealis. Information regarding its cultivation, growth time, or effects is entirely unrelated to the study of auroras. For details on that topic, one would need to consult specialized horticultural or cannabis-specific resources. This website is dedicated solely to the science and wonder of the natural light show in our planet’s polar skies.

Quick Facts

- A typical aurora burst lasts for about 15-40 minutes.

- Major geomagnetic storms can produce aurora displays that last all night.

- The duration is controlled by the solar wind and the orientation of its magnetic field (Bz).

- A persistent ‘southward Bz’ is the key ingredient for a long-lasting aurora.

- The term ‘Northern Lights’ can refer to the Aurora Borealis or a cannabis strain; this article is about the natural phenomenon only.

- Aurora displays are not continuous; they often occur in waves or bursts of activity.

- Patience is key for aurora watching, as a quiet sky can become active later in the night.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Is there a best time of night to see a long-lasting aurora? A: While auroras can happen at any time during darkness, the most active periods are often centered around ‘magnetic midnight’, which is typically between 10 PM and 2 AM local time. This is when you are most likely to be under the most active part of the auroral oval.

Q: How can I know if an aurora display is likely to be long? A: You can monitor space weather forecasts from sources like the NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center. Look for alerts about incoming CMEs or high-speed solar wind streams, and check the real-time Bz value. A strong, sustained negative Bz value suggests conditions are ripe for a long display.

Q: Does the aurora ‘use up’ its energy and fade? A: Yes, in a way. An auroral substorm is a process where the magnetosphere releases built-up energy from the solar wind. Once that energy is discharged as an aurora, things may quiet down until more energy is loaded into the system, which can then trigger another display.

Other Books

- NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center – Official Forecasts

- SpaceWeatherLive – Real-time Auroral and Solar Data

- University of Alaska Fairbanks – Geophysical Institute FAQ

Cosmic Tug-of-War: Magnetic Fields Move Worlds

Summary

By the end of this article, you will understand the invisible magnetic web that connects stars and planets, a force so powerful it can create cosmic shocks, cause stellar storms, and even drag entire planets out of their orbits.

Quick Facts

- A planet orbiting close enough to its star moves through a dense magnetic 'atmosphere', creating a shockwave like a boat moving through water.

- This magnetic connection can transfer enough energy to create a bright 'hot spot' on the star's surface that follows the planet's orbit.

- The magnetic drag is so strong it can cause planets to migrate, either spiraling into their star or being pushed further away over millions of years.

- A planet's own magnetic field acts like a shield; its orientation (north pole up or down) drastically changes the strength of the interaction.

- Astronomers have noticed a 'dearth' of close-in planets around fast-rotating stars, possibly because this magnetic interaction has already pulled them into the star.

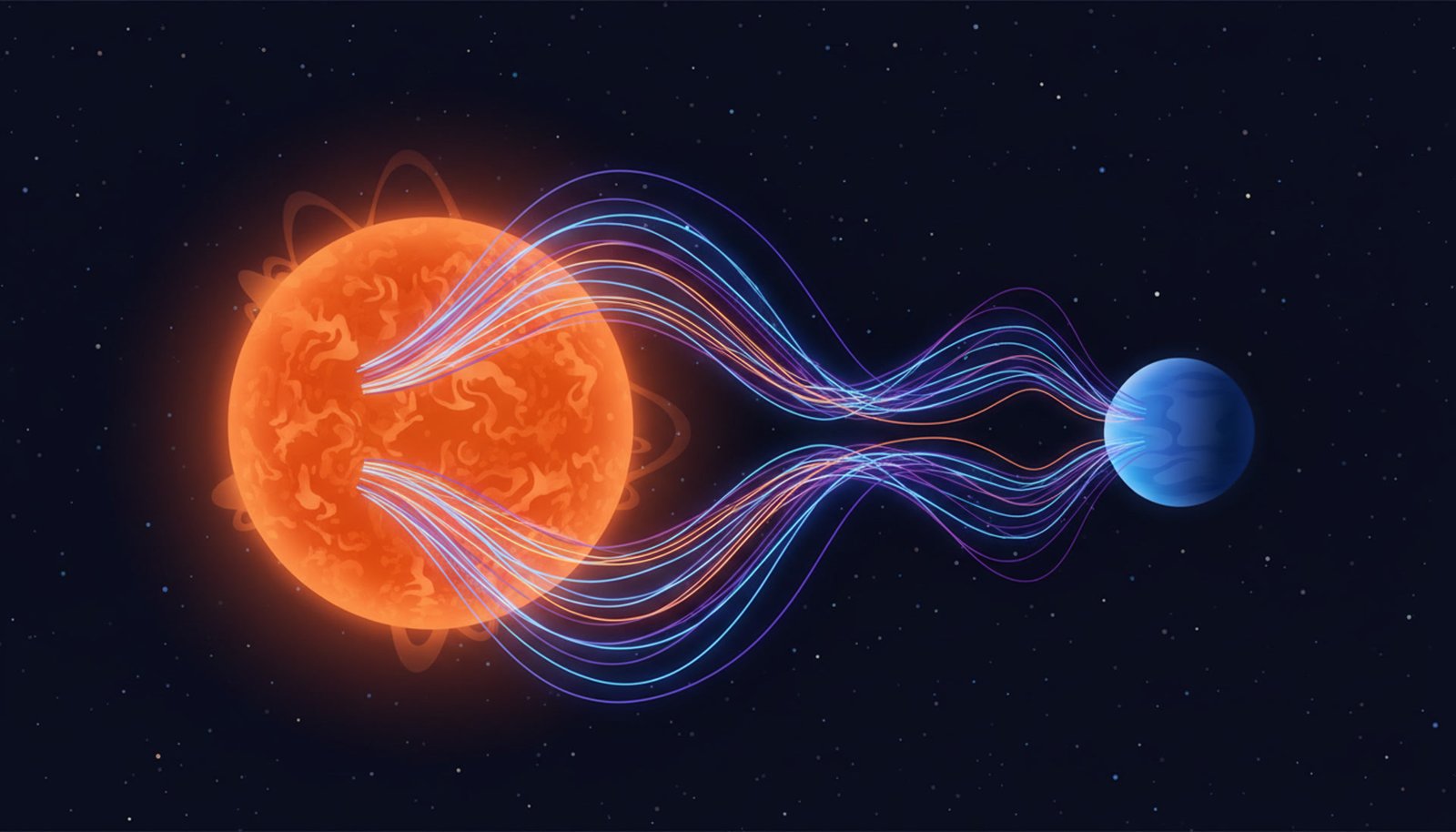

The Discovery: More Than Just Gravity

When astronomers began discovering thousands of ‘hot Jupiters’—gas giants orbiting incredibly close to their stars—they found phenomena that gravity alone couldn’t explain. The Story began with puzzling observations: some host stars showed strange, synchronized flare-ups, while others seemed to have ‘cleared out’ zones with no close-in planets. Scientists realized these planets were so close they were orbiting *inside* the star’s extended magnetic field. This triggered a wave of research into star-planet magnetic interaction (SPMI). The models reviewed in this paper show how this interaction can explain the mysteries: planets ‘poking’ their stars to cause flares, and a magnetic ‘drag’ so powerful it could make planets spiral to their doom, explaining the empty zones.

Original Research Paper: ‘Models of Star-Planet Magnetic Interaction’

Magnetic interactions are today a serious candidate to explain these fascinating phenomena.

— Antoine Strugarek, Astrophysicist

The Science Explained Simply

Imagine a planet so close to its star that the star’s magnetic field is stronger than the stellar wind pushing outwards. This is the sub-Alfvénic regime. Now, this isn’t just a static field; it’s a dynamic plasma environment. As the planet orbits, it plows through this magnetic medium, creating a disturbance. The key concept is the Alfvén Wing. Instead of the disturbance spreading out, the energy gets focused and channeled along the magnetic field lines, creating two ‘wings’ that connect back to the star. This is NOT like a simple magnetic attraction. It’s an active, energetic connection that transfers momentum and power, acting like both a brake and a generator. It’s a constant, powerful interaction driven by the planet’s motion.

A close-in planet can be viewed as a perturber orbiting in the likely non-axisymmetric inter-planetary medium.

— Antoine Strugarek, Astrophysicist

The Aurora Connection

The beautiful auroras on Earth happen when the solar wind interacts with our planet’s magnetic field, channeling energy and particles into our atmosphere. Star-planet magnetic interaction is this exact process, scaled up to an incredible degree. The Alfvén wings are like the magnetic field lines that guide particles to Earth’s poles, but they carry vastly more energy. When this energy slams back into the star’s atmosphere, it can create a starspot—a stellar aurora. When it hits the planet’s atmosphere, it can trigger planetary auroras that would be thousands of times more powerful than our own. Studying these extreme interactions helps us understand the fundamental physics that protects Earth’s atmosphere and gives us our own gentle light shows.

A Peek Inside the Research

Modeling these interactions is incredibly hard. Early researchers used clever analogies, like treating the star-planet system as a simple electric circuit (the ‘unipolar inductor’ model). The planet’s motion acted as a generator, the magnetic field lines were the wires, and the planet and star were resistances. While useful, this was too simple. The real progress came from 3D magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) simulations. These are complex computer models that treat the star’s wind as a magnetized fluid. Researchers spend immense effort creating realistic ‘boundary conditions’ for the planet and star to ensure the simulation is accurate. These models, like those shown in the paper, are the tools that allow us to visualize the invisible magnetic games playing out between stars and their planets.

Key Takeaways

- Gravity isn't the only major force in solar systems; star-planet magnetic interaction (SPMI) is critical for close-in planets.

- 'Alfvén wings' are channels of energy that flow along magnetic field lines between a star and a planet, similar to a current in a wire.

- The interaction depends on whether the planet is magnetized ('dipolar') or not ('unipolar'). A magnetized planet has a shield, a non-magnetized one gets permeated.

- Observing the effects of SPMI, like pre-transit dips in starlight, could be one of the best ways to detect magnetic fields on distant exoplanets.

- These magnetic forces can heat planets, strip their atmospheres, and influence their entire evolutionary path.

Sources & Further Reading

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Can this magnetic interaction happen between the Sun and Earth?

A: Yes, but it’s much, much weaker. Earth is far outside the Sun’s sub-Alfvénic zone, where the solar wind dominates. The interactions described in the paper are for exoplanets orbiting hundreds of times closer to their star than Earth does to the Sun.

Q: Can we actually see these magnetic fields?

A: Not directly, but we can see their effects. We can look for synchronized stellar flares, absorption of starlight from a planet’s bow shock just before it transits, or radio emissions from the planetary aurorae. These are the observable clues that tell us the magnetic interactions are happening.

Q: Could this force eventually destroy a planet?

A: Absolutely. The magnetic torque can cause a planet’s orbit to decay, making it spiral closer and closer to its host star until it’s consumed. This is a leading theory for why we don’t find many planets in extremely close orbits around certain types of stars.

Can you see the northern lights every night?

Can You See the Northern Lights Every Night?

The dream of many travelers is to stand under a sky dancing with the ethereal green and purple hues of the Northern Lights. A common question is whether this spectacular display is a nightly event in the Arctic. While the aurora is a more frequent visitor to the polar skies than anywhere else, it is far from a guaranteed nightly show.

Seeing the aurora is like trying to catch a glimpse of a shy, wild animal; it requires patience, preparation, and a bit of luck. The appearance of the Northern Lights depends on a delicate interplay between the Sun’s activity, Earth’s magnetic field, and our local weather conditions. This guide breaks down the essential ingredients you need for a successful aurora hunt.

The Three Essential Ingredients for an Aurora Sighting

For the Northern Lights to be visible, three distinct conditions must be met simultaneously. If even one of these is missing, you won’t see the show, no matter how strong the solar storm.

Ingredient 1: Darkness (The Right Time & Place)

The aurora is a relatively faint phenomenon compared to the light from our sun or even a full moon. Therefore, the first requirement is complete darkness. This is why you cannot see the aurora during the day. In the high latitudes of the ‘auroral zone’, this also means you can’t see them during the summer months due to the Midnight Sun, when the sun never fully sets. The prime aurora viewing season runs from late August to early April. Additionally, you must get away from light pollution from cities and towns, which can easily wash out the aurora’s glow. Finding a remote spot with an unobstructed view of the northern horizon is critical.

Ingredient 2: Clear Skies (The Weather Factor)

This is often the most frustrating factor for aurora hunters. The Northern Lights occur very high in the atmosphere, between 60 to 200 miles (100-320 km) above the Earth’s surface. This is far above any weather or clouds. A strong aurora can be dancing brilliantly in the sky, but if there is a thick layer of cloud cover, you will not see a thing from the ground. Before heading out, it’s just as important to check the local weather forecast as it is to check the aurora forecast. A clear sky is non-negotiable. Sometimes, even a short drive of 20-30 minutes can be enough to escape a localized patch of clouds and find a clear viewing window.

Ingredient 3: Solar Activity (The Space Weather Factor)

The aurora is caused by charged particles from the sun—the solar wind—interacting with Earth’s magnetosphere. The strength and speed of this solar wind vary constantly. For a vibrant aurora to occur, there needs to be a significant stream of these particles hitting our atmosphere. This activity is measured on the Kp-index, a scale from 0 to 9. A Kp-index of 0-2 means very low activity, while a Kp of 4 or higher can produce a bright, active display visible across the auroral zone. This geomagnetic activity is unpredictable, driven by events on the sun like coronal mass ejections (CMEs). Following a space weather forecast is essential to know if the sun is providing the necessary fuel for the light show.

Maximizing Your Chances of a Sighting

While you can’t control the sun or the weather, you can control your preparation and strategy to significantly increase your odds of seeing the lights.

Choose the Right Location

Your geographical position is paramount. You need to be within the auroral oval, a ring-shaped zone centered on the magnetic north pole. Prime locations include northern Norway, Sweden, and Finland; Iceland; northern Canada (like Yukon and Northwest Territories); and Alaska. During periods of very high solar activity (a strong geomagnetic storm), this oval expands, and the lights can be seen from lower latitudes, but for the best and most consistent chances, you must travel north. The further you are inside this zone, the more likely you are to see the aurora even with lower Kp-index values.

Be Patient and Persistent

The aurora does not run on a schedule. It can appear for just a few minutes or dance for hours. The most common viewing window is between 10 PM and 2 AM local time, but it can happen at any time during the dark hours. The key is to be patient. Find a comfortable spot, dress in very warm layers, and be prepared to wait. Many successful sightings come after hours of waiting in the cold. Planning a trip with multiple nights dedicated to aurora hunting dramatically increases your chances, as it gives you more opportunities to get a night with clear skies and good solar activity.

Quick Facts

- You cannot see the Northern Lights every night; it’s a special event requiring specific conditions.

- Three things must align: darkness, clear skies, and sufficient solar activity.

- The best season for aurora viewing is from late August to early April when the nights are long and dark.

- Cloud cover is the number one obstacle; the aurora can be active above the clouds, but you won’t see it.

- Solar activity is measured by the Kp-index; a value of 4 or higher is considered a strong display.

- Location is critical: you must be within the ‘auroral oval’ in places like Iceland, northern Scandinavia, or Alaska.

- Patience is key. Plan for multiple nights and be prepared to wait, typically between 10 PM and 2 AM.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What time of night is best for seeing the aurora? A: While the aurora can appear at any time when it’s dark, the most active displays typically occur between 10 PM and 2 AM local time. This window is often referred to as ‘magnetic midnight’.

Q: Does a full moon prevent you from seeing the Northern Lights? A: A bright full moon can make the sky less dark, which can wash out faint auroras. However, a strong and vibrant aurora display will still be clearly visible, and the moonlight can beautifully illuminate the landscape for photography.

Q: Can the aurora be active even if I can’t see it? A: Yes, absolutely. The aurora is often active high in the atmosphere but may be too faint for the human eye to detect, especially if there’s light pollution. It could also be happening on the other side of the planet or be completely obscured by clouds.

Q: How far in advance can you forecast the Northern Lights? A: General long-term forecasts can predict active periods based on the sun’s rotation (27 days). However, reliable, short-term forecasts are typically only available 1 to 3 days in advance, after a solar event like a CME has occurred and is heading toward Earth.

Other Books

- NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center – Aurora Forecast

- Space.com – Where and When to See the Aurora

- Travel Alaska – Tips for Viewing the Northern Lights

Earth's Magnetic GPS: Mapping the Aurora

Summary

By the end of this article, you will understand why your compass doesn’t point to the geographic North Pole and how scientists use special ‘magnetic maps’ to track space weather and predict where the aurora will appear.

Quick Facts

- Earth's magnetic field is not perfectly aligned with its rotation axis; it's tilted.

- The magnetic poles are constantly moving, requiring scientists to update their maps every five years.

- By convention, we call the pole in the north the 'magnetic north pole', but the actual dipole axis of Earth's field points southward.

- The most precise magnetic 'grids' (like QD coordinates) are non-orthogonal, meaning their lines don't intersect at 90-degree angles, especially in the South Atlantic.

- Magnetic Local Time (MLT) is a system where 'noon' is defined by the Sun's position relative to the magnetic field, not geographic longitude.

The Discovery: Beyond the Bar Magnet

For centuries, we’ve known Earth acts like a giant bar magnet. Scientists first built coordinate systems based on this simple idea, called Centered Dipole (CD) coordinates. It was a good start, but observations of space phenomena didn’t quite line up. So, they created a more refined model where the ‘bar magnet’ was shifted from the Earth’s center—the Eccentric Dipole (ED) model. But even that wasn’t enough. The real magnetic field is complex and lumpy. The breakthrough came when scientists abandoned simple magnets and started using computers to trace the actual magnetic field lines from the full International Geomagnetic Reference Field (IGRF). This created incredibly accurate but mathematically tricky systems like Corrected Geomagnetic (CGM) and Quasi-Dipole (QD) coordinates, which are now essential for modern space science.

Original Paper: ‘Magnetic Coordinate Systems’ in Space Science Reviews

The improved accuracy comes at the expense of simplicity, as the result is a non-orthogonal coordinate system.

— K.M. Laundal & A.D. Richmond

The Science Explained Simply

Imagine a regular map grid where every line of latitude and longitude crosses at a perfect 90-degree angle. That’s an orthogonal system. Now, imagine stretching and warping that grid in some places. The lines would no longer be perpendicular. That’s a non-orthogonal system, and it’s exactly what the most accurate magnetic coordinates are like. This is NOT a mistake; it’s a true representation of Earth’s complex field. The key idea is that these coordinates are constant along a given magnetic field line. So if you travel up or down a field line, your Quasi-Dipole latitude and longitude don’t change. This makes them incredibly powerful for studying things like the aurora, which are guided by these very lines.

The deviation from orthogonality is particularly significant in the South Atlantic and in the southern parts of Africa.

— K.M. Laundal & A.D. Richmond

The Aurora Connection

The aurora is like a giant neon sign in the sky, lit up by charged particles from the solar wind that are guided by Earth’s magnetic field. If you plot auroral sightings on a regular geographic map, they appear in a scattered, messy pattern. But if you use a magnetic coordinate system like Corrected Geomagnetic (CGM) coordinates, the pattern snaps into focus: a perfect ring around the magnetic pole, known as the auroral oval. This is because the particles follow the magnetic field lines, not lines of geographic longitude. These coordinate systems are the ‘Rosetta Stone’ that allows us to understand the shape, location, and dynamics of the aurora, connecting what we see in the sky to the vast magnetic structures that protect our planet.

A Peek Inside the Research

Scientists can’t just ‘look’ at a magnetic field line. The work involves complex computation. They start with the International Geomagnetic Reference Field (IGRF), a global model built from satellite and ground-based magnetometer data. Using this model, they perform a process called field line tracing. A computer program starts at a specific point in the ionosphere (e.g., 110 km altitude) and calculates the direction of the magnetic field vector. It then takes a small step in that direction, recalculates, and repeats, stepping along the invisible magnetic line through space. By tracing this line to its highest point (the apex) or to where it crosses the equator, they can define accurate magnetic coordinates. This hard computational work is what makes modern, precise space weather forecasting possible.

Key Takeaways

- Geospace phenomena like the aurora are organized by the magnetic field, not geography.

- Scientists use different magnetic coordinate systems for different purposes, from simple dipole models for deep space to complex ones for the ionosphere.

- Simple models (like Centered Dipole) treat Earth like a perfect bar magnet, which is a good first approximation.

- Advanced models (like Quasi-Dipole) trace the real, messy magnetic field lines for high accuracy near Earth.

- Using vectors in advanced, non-orthogonal magnetic coordinates requires special mathematical handling to avoid errors.

Sources & Further Reading

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why are there so many different magnetic coordinate systems?

A: Different systems are tools for different jobs and different regions of space. Simple ‘dipole’ systems are good for high altitudes where the field is simple, while complex ‘field-line traced’ systems are needed for accuracy in the ionosphere where the aurora happens.

Q: What’s the difference between the magnetic pole and the geomagnetic pole?

A: The ‘magnetic pole’ (or dip pole) is where the field lines point straight down, which is what a compass would lead you to. The ‘geomagnetic pole’ is a theoretical concept based on the best simple dipole approximation of Earth’s field. They are in different locations and both move over time.

Q: Do I need to worry about this for my compass?

A: For basic navigation, your compass works fine by pointing to the magnetic dip pole. These advanced coordinate systems are specialized tools for scientists studying plasma physics and space weather on a global scale.