What are northern lights in Toronto?

Can You See the Northern Lights in Toronto?

Seeing the vibrant, dancing curtains of the Aurora Borealis is a bucket-list dream for many. While typically associated with Arctic locations like Iceland or Norway, the question often arises: can this celestial spectacle ever grace the skies of a southern Canadian city like Toronto? The answer is a hopeful, but conditional, yes.

Toronto lies far south of the Earth’s ‘auroral oval’, the region where auroras are a common sight. However, during periods of intense solar activity, this oval can expand dramatically, bringing the Northern Lights to lower latitudes. This guide explains the science behind why it’s so rare and provides practical tips for chasing this elusive sight in the Greater Toronto Area.

The Challenges: Why Toronto Isn't an Aurora Hotspot

Several major factors work against aurora sightings in Toronto. Understanding them is key to knowing what it takes for a successful viewing.

Geographic Latitude and the Auroral Oval

The Northern Lights occur within a ring around the Earth’s geomagnetic north pole known as the auroral oval. This oval typically covers northern Canada, Alaska, Scandinavia, and Siberia. Toronto’s geomagnetic latitude is simply too low for it to be under this oval on a normal night. For the aurora to be visible, a massive geomagnetic storm, fueled by a Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) from the sun, must hit Earth. This storm can energize and expand the auroral oval southward, sometimes stretching it down over southern Ontario and the northern United States, making a rare sighting possible.

The Battle Against Light Pollution

Even if a powerful storm pushes the aurora south, Toronto’s biggest challenge is light pollution. As one of North America’s largest metropolitan areas, the ambient light from buildings, streetlights, and cars creates a perpetual skyglow that washes out all but the brightest celestial objects. Auroras visible from this latitude are often faint and low on the northern horizon. This delicate light is easily obscured by the city’s glow. To see them, you must escape the city core. The brightness of the sky is often measured on the Bortle Scale, where Toronto’s core is a Class 8 or 9 (the brightest), making aurora viewing nearly impossible.

The Need for Extreme Space Weather

Regular solar wind causes the everyday aurora in the far north. For Toronto, we need an extraordinary event. The strength of a geomagnetic storm is measured on the Kp-index, a scale from 0 to 9. A typical night in the north might see auroras at Kp 2 or 3. For a faint glow to be visible on the horizon in Toronto, a storm of at least Kp 7 (‘Strong’) is required. For a truly impressive, overhead display (an exceptionally rare, once-in-a-decade event), a Kp 8 or 9 (‘Severe’ or ‘Extreme’) storm would be necessary. These powerful events are most common during the solar maximum, the peak of the Sun’s 11-year activity cycle.

How to Maximize Your Chances in Southern Ontario

If the conditions align, you can take steps to increase your odds of witnessing this rare spectacle.

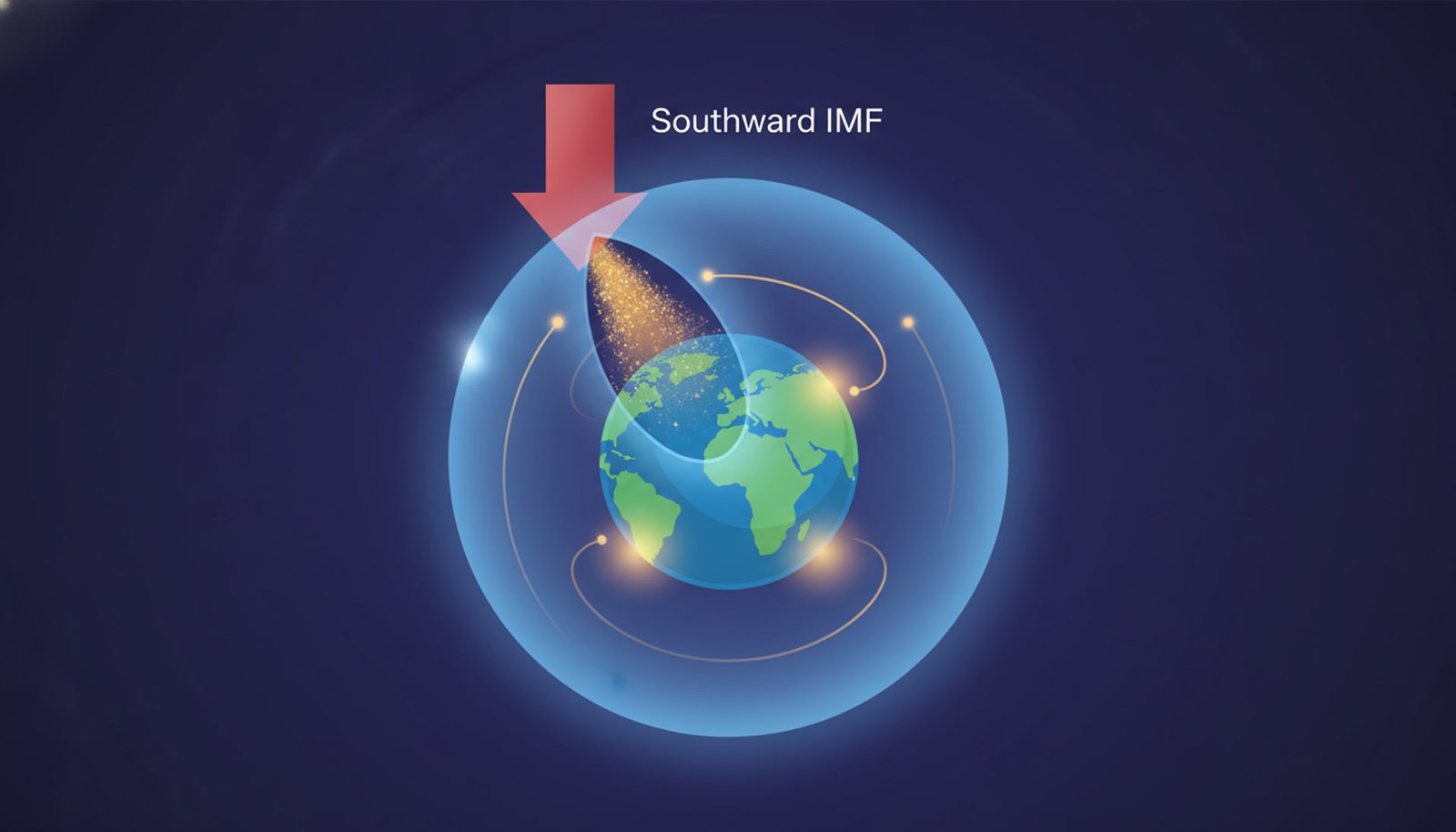

Monitor Space Weather Forecasts

You can’t see the aurora if you don’t know it’s happening. Use resources like the NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) or apps like ‘My Aurora Forecast’. Look for alerts indicating a high Kp-index (7 or above). Other key indicators to watch for are a high solar wind speed (above 600 km/s) and a strongly negative Bz component (the direction of the interplanetary magnetic field). A southward Bz (negative value) is crucial as it allows solar particles to connect with Earth’s magnetic field more effectively, fueling a stronger storm and brighter aurora.

Escape the City and Look North

Your number one priority is to get away from city lights. Drive at least an hour or two north or east of the GTA. Look for locations with a clear, unobstructed view of the northern horizon. Provincial parks, conservation areas, or rural farmland are ideal. Places like the Torrance Barrens Dark-Sky Preserve near Gravenhurst are specifically designated for their dark skies and are excellent, though distant, options. Even getting to the north shore of Lake Simcoe can make a significant difference. The darker your location, the better your eyes can adapt and detect the faint auroral glow.

Manage Your Expectations and Use a Camera

When viewed from southern Ontario, the aurora might not look like the vibrant, dancing ribbons you see in photos. To the naked eye, a strong display might appear as a faint, greyish-white or greenish glow on the northern horizon, sometimes with subtle vertical pillars of light. Our eyes are not very sensitive to color in low light. However, a DSLR or mirrorless camera on a tripod can reveal the true colors. Use a long exposure setting (e.g., 10-20 seconds), a wide aperture (e.g., f/2.8), and a high ISO (e.g., 1600-3200) to capture the vivid greens and purples your eyes might miss.

Quick Facts

- Seeing the aurora in Toronto is possible but extremely rare, requiring a major geomagnetic storm.

- A Kp-index of 7 or higher is the minimum required for a potential sighting on the northern horizon.

- Severe light pollution from the city is the biggest obstacle; you must get to a dark location outside the GTA.

- Always look for a clear, unobstructed view to the north.

- To the naked eye, the aurora may appear as a faint, colorless glow, not the vibrant colors seen in photos.

- Use a camera with long exposure settings to capture the aurora’s true colors and structure.

- Sightings are more likely during the solar maximum, the peak of the Sun’s 11-year activity cycle.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: How often can you see the Northern Lights in Toronto? A: Visible displays are very infrequent. A faint glow on the horizon might be possible a few times a year during the peak of the solar cycle, but a significant, memorable display might only happen once every 5-10 years.

Q: What is the best time of year to look for them? A: The aurora is caused by solar activity, which can happen any time. However, your chances are best during the months around the spring and fall equinoxes (March/April and September/October) due to favorable alignments of Earth’s magnetic field.

Q: Can I see the aurora from my apartment balcony in downtown Toronto? A: It is virtually impossible. The extreme light pollution in downtown Toronto will completely wash out any aurora except for perhaps a once-in-a-century superstorm. You must leave the city to have any realistic chance.

Other Books

- NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center – Aurora Forecast

- Dark Site Finder – Light Pollution Map

- Space.com: Auroras at lower latitudes

Auroral Whirlpools: The Hidden Electric Dance

Summary

By the end of this article, you will understand why auroras don’t just hang there as curtains, but can form stunning street-like patterns of whirlpools, and how this is driven by a complex electrical circuit connecting Earth to deep space.

Quick Facts

- Surprise: These beautiful auroral whirlpools can form in less than a minute.

- The aurora isn't just light; it's the visible part of a giant electrical circuit in the sky.

- Surprise: The swirling is caused by a tug-of-war between two different types of horizontal currents in the ionosphere.

- These vortices are often the first sign of an explosive release of energy called an auroral substorm.

The Discovery: Cracking the Auroral Code

Scientists have long observed that at the start of a powerful auroral display (a substorm), simple arcs of light can suddenly brighten, split, and twist into a row of swirling vortices. But what causes this rapid, beautiful chaos? To solve this, Dr. Yasutaka Hiraki didn’t use a telescope. He used a supercomputer. The Story of this discovery is one of digital recreation. He created a 3D simulation of the ionosphere, placed a simple auroral arc inside it, and then simulated a surge of energy from space—an enhanced electric field. The result was stunning: the simulated arc buckled and deformed into a perfect vortex street in just 30-40 seconds, matching real-world observations. By analyzing the flow of currents in his simulation, he pinpointed the exact electrical feedback loop responsible for the dance.

Ionospheric current system accompanied by auroral vortex streets – Hiraki, Y. (2016)

Our previous work reported that an initially placed arc intensifies, splits, and deforms into a vortex street during a couple of minutes, and the prime key is an enhancement of the convection electric field.

— Yasutaka Hiraki, Author

The Science Explained Simply

This swirling isn’t just a random pattern. It’s caused by a specific process called Cowling Polarization. To understand it, let’s build a fence around the concept: this is NOT like water swirling down a drain. It’s an electrical feedback loop. Imagine two types of currents flowing horizontally in the ionosphere: the Hall current and the Pedersen current. When a bright aurora forms, it acts like a roadblock for the main Hall current. This causes electrical charge to pile up on the edges of the aurora. This pile-up creates a *new* electric field. This new field then drives a Pedersen current, which flows in a different direction and helps complete the circuit. The interaction between the original current, the roadblock, and the new current is what kicks off the spinning motion that forms the vortex.

One component is due to the perturbed electric field by Alfvén waves, and the other is due to the perturbed electron density (or polarization) in the ionosphere.

— Yasutaka Hiraki, Author

The Aurora Connection

These vortex streets, while appearing as local phenomena, are deeply connected to the grand-scale behavior of Earth’s magnetic field. They are the ionospheric footprints of Alfvén waves—powerful magnetic waves that travel from the Earth’s distant magnetotail, a region where immense energy from the solar wind is stored. When this stored energy is suddenly released during a substorm, it sends these waves racing towards Earth. The waves deliver the extra energy and electric field that destabilize the calm auroral arcs. So, when you see a vortex, you’re witnessing the precise moment that energy from millions of miles away makes its dramatic entrance into our atmosphere, all guided by the invisible architecture of our planet’s magnetic shield.

A Peek Inside the Research

This research is a perfect example of how modern science uses Knowledge and Tools. The core of this work is a ‘three-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) simulation’. This is a fancy way of saying they created a virtual box of plasma (the superheated gas that makes up the aurora) and programmed in the fundamental laws of physics that govern how electricity, magnetism, and fluids interact. They then set the initial conditions—a calm atmosphere with a simple auroral arc—and pressed ‘play’. By observing how this digital aurora evolved when ‘poked’ by an external electric field, they could dissect the complex, high-speed chain of events in a way that is impossible to do by just looking at the sky.

Key Takeaways

- Salient Idea: Auroral shapes are dictated by the delicate balance of invisible electrical currents.

- Magnetic waves, called Alfvén waves, act as messengers, carrying energy from deep space down to our atmosphere.

- A process called 'Cowling Polarization' creates a feedback loop where currents generate new electric fields, which in turn drive new currents, causing the swirls.

- Computer simulations are essential for untangling these fast, complex interactions that we can't fully see with cameras alone.

Sources & Further Reading

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why do the vortices form in a ‘street’ or a row?

A: This pattern, known as a von Kármán vortex street, is common in fluid dynamics when a flow is disturbed. The instability in the auroral arc naturally settles into this organized, repeating pattern of counter-rotating swirls, which is the most energy-stable configuration.

Q: Can we see these auroral whirlpools with the naked eye?

A: Yes, but it requires a very active and fast-moving aurora. They happen quickly, so they are often better captured by sensitive, high-speed cameras that can reveal the swirling structure that might look like a chaotic flicker to our eyes.

Q: What’s the difference between Pedersen and Hall currents?

A: In the ionosphere, an electric field pushes charged particles. The Pedersen current flows in the direction of this electric field. However, because of Earth’s magnetic field, electrons are deflected sideways, creating the Hall current, which flows perpendicular to both the electric and magnetic fields.

What is northern lights TV show about?

Northern Lights on TV: The Real Science Behind the Spectacle

You might have searched for information on a ‘Northern Lights TV show’ and found yourself here. It’s a popular title for dramas and thrillers, often using the aurora’s beauty and mystery as a backdrop. While those stories are captivating, the true story of the Northern Lights is a scientific epic that unfolds 93 million miles away and ends in a breathtaking light show in our planet’s sky.

This article explores how the aurora is portrayed in popular culture and then dives into the even more incredible science behind the real thing. We’ll separate the on-screen fiction from the astronomical facts to reveal what’s really happening during an auroral display.

The Aurora in Popular Culture

The Northern Lights have long captured the human imagination, making them a perfect element for storytelling in television and film. Their mysterious, ethereal quality provides a stunning backdrop for drama, romance, and suspense.

Common Themes in TV and Film

In media, the aurora is often used as a powerful symbolic device. It can represent magic, a connection to the spiritual world, a turning point in a character’s life, or an omen of things to come. For example, a TV show might use the appearance of the lights to coincide with a major plot twist or a moment of profound realization for a character. The setting is typically a remote, cold, and isolated location, which uses the aurora to amplify feelings of both beauty and isolation. Many fictional works, including recent TV series titled ‘Northern Lights’, leverage this dramatic potential, weaving the natural wonder into the fabric of their narrative to enhance the mood and atmosphere.

Separating On-Screen Fiction from Reality

While visually stunning, portrayals of the aurora on TV often take creative liberties. A common trope is characters ‘hearing’ the lights—a crackling or humming sound. In reality, the aurora occurs in the near-vacuum of the upper atmosphere, more than 60 miles (100 km) up, where it’s too thin for sound to travel to the ground. Another fictional element is attributing supernatural powers or direct influence over events to the aurora. While a strong geomagnetic storm (the cause of the aurora) can affect technology like satellites and power grids, the lights themselves are simply a beautiful result of physics and pose no direct danger or magical influence to people on the surface.

The Real 'Show': How the Aurora is Produced

The true story of the Northern Lights is a fascinating journey of energy and particles across the solar system. It’s a multi-stage process that turns invisible forces into the greatest light show on Earth.

Act 1: The Solar Wind

The show begins at our star, the Sun. The Sun constantly emits a stream of charged particles, mostly electrons and protons, known as the solar wind. This ‘wind’ travels through space at speeds of around one million miles per hour. Sometimes, the Sun has larger eruptions, called Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs), which hurl vast clouds of these particles toward the planets. It is these powerful CMEs that are responsible for the most intense and widespread auroral displays, often visible much further south than usual. This journey from the Sun to Earth typically takes one to three days.

Act 2: Earth’s Magnetic Shield

When the solar wind reaches Earth, it first encounters our planet’s protective magnetic field, the magnetosphere. This invisible field, generated by the Earth’s molten outer core, deflects the majority of the harmful particles safely around the planet. However, the magnetosphere is weakest at the North and South Poles. Like a giant funnel, the magnetic field lines guide the solar wind particles down towards the polar regions, channeling them into the upper atmosphere where the final act of the light show takes place. This is why the aurora is concentrated in rings around the poles, known as the auroral ovals.

The Grand Finale: Atmospheric Collisions

As the trapped solar particles spiral down into the atmosphere, they collide with gas atoms and molecules, primarily oxygen and nitrogen. These collisions transfer energy to the atmospheric gases, ‘exciting’ them. To return to their normal state, the excited atoms must release this excess energy in the form of light particles called photons. The color of the light depends on which gas was hit and at what altitude. Green, the most common color, is from oxygen at 60-150 miles high. Red is from high-altitude oxygen (above 150 miles), while pinks and purples are often from nitrogen. Billions of these collisions create the shimmering curtains of light we see as the aurora.

Quick Facts

- The term ‘Northern Lights’ is used for various TV shows, but the real aurora is a natural light display.

- The aurora is caused by charged particles from the sun (solar wind) interacting with Earth’s magnetosphere.

- Fictional portrayals often include sounds or magical properties, which are not scientifically accurate.

- The different colors of the aurora are determined by which atmospheric gas (oxygen or nitrogen) is struck by solar particles and at what altitude.

- The lights are concentrated in ‘auroral ovals’ around the magnetic poles due to Earth’s magnetic field.

- Intense auroras are often caused by major solar events called Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs).

- While the aurora itself is harmless, the underlying geomagnetic storms can impact satellites and power grids.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Are there any actual TV shows called ‘Northern Lights’? A: Yes, several TV shows, series, and movies have used the title ‘Northern Lights’. They are typically dramas or thrillers that use the aurora as a scenic or symbolic backdrop for a fictional story.

Q: Can the real aurora look as vibrant as it does on TV? A: Absolutely. During a strong geomagnetic storm, the aurora can be incredibly bright and fast-moving, looking just as spectacular as any special effect. However, what we see with the naked eye can sometimes be less colorful than what a camera captures in a long-exposure photograph.

Q: Are documentaries about the Northern Lights accurate? A: Generally, yes. Documentaries from reputable sources like PBS, BBC, National Geographic, or NASA provide scientifically accurate and fascinating insights into the physics behind the aurora and the efforts to study it.

Other Books

- NASA: What is an Aurora?

- IMDb: Example of a ‘Northern Lights’ TV Series

- NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center – Aurora Dashboard

Electron Showers Lower the Aurora's Ignition Point

Summary

By the end of this article, you will understand the hidden feedback loop that makes auroras suddenly explode in brightness, and why a ‘rain’ of electrons is the key to flipping the switch.

Quick Facts

- Auroras don't just 'turn on'; they need a strong enough 'push' from an electric field to intensify.

- Previous theories predicted this 'push' needed to be much stronger than what we actually observe in nature.

- The missing piece was a 'rain' of electrons that changes the electrical properties of the atmosphere.

- This electron shower makes the atmosphere more conductive, like adding salt to water.

- This increased conductivity lowers the 'ignition threshold' for an aurora by more than 50%.

The Discovery: Solving an Auroral Puzzle

For years, scientists were puzzled. Their models showed that for a quiet auroral arc to erupt into a dazzling display, it needed a very strong ‘push’ from a background electric field—about 25 to 45 millivolts per meter (mV/m). Yet, real-world radar observations showed these intensifications happening at much lower levels, around 10-20 mV/m. There was a disconnect between theory and reality. Dr. Yasutaka Hiraki’s research presents the Story of the solution. He introduced a crucial, previously under-appreciated effect: the ionization caused by precipitating electrons. These falling electrons energize the atmosphere, making it a better conductor. This single change in the model dramatically lowered the required energy threshold, perfectly aligning the theory with real-world observations.

It was found that the threshold of convection electric fields is significantly reduced by increasing the ionization rate.

— Yasutaka Hiraki, Researcher

The Science Explained Simply

Imagine Earth’s connection to space as a giant electrical circuit. The magnetosphere is the power source, and the ionosphere (our upper atmosphere) is like a resistor. Energy travels down this circuit via Alfvén waves. Now, this is NOT just about the waves delivering power. The key idea is that as these waves hit the atmosphere, they cause electrons to ‘precipitate’ or rain down. This rain of electrons ionizes the neutral air, which dramatically *lowers* the atmosphere’s electrical resistance. With lower resistance, the same amount of power from the magnetosphere can drive a much stronger current and amplify the Alfvén waves even more. This creates a runaway feedback loop, causing the aurora to suddenly and intensely brighten. It’s a self-fueling process.

The Aurora Connection

This research directly explains one of the most beautiful sights in the Arctic: the explosive onset of an auroral substorm. You might see a faint, quiet green arc hanging in the sky for minutes. Then, seemingly without warning, it erupts into swirling, dancing curtains of light that fill the sky. That sudden change is the moment the system crosses the now-lowered threshold. The positive feedback loop kicks in, the Alfvén wave instability grows exponentially, and the energy flowing down Earth’s magnetic field lines intensifies dramatically. The electron ‘rain’ didn’t just add to the light; it changed the rules of the game, allowing the main event to begin with less of a push.

The prime key is an enhancement of plasma convection, and the convection electric field has a threshold.

— Yasutaka Hiraki, Researcher

A Peek Inside the Research

This breakthrough didn’t come from a new telescope, but from powerful computer modeling and theoretical physics. Dr. Hiraki used a set of complex mathematical equations to simulate the magnetosphere-ionosphere (M-I) coupling system. This ‘digital twin’ of the auroral circuit allowed him to change one variable at a time. He modeled how Alfvén waves propagate and interact with the ionosphere. The crucial step was adding a term to his equations representing the ionization from precipitating electrons (the ‘q’ value). By running simulations with different ‘q’ values, he demonstrated precisely how this effect lowered the instability threshold, providing a clear, mathematical explanation for a long-standing mystery in space physics.

Key Takeaways

- Auroral intensification is driven by an instability of energy waves (Alfvén waves) traveling along Earth's magnetic field lines.

- Electron precipitation creates a positive feedback loop: the waves cause electrons to fall, which in turn makes it easier for the waves to grow stronger.

- The ionosphere isn't a static resistor in a cosmic circuit; its conductivity is dynamic and changes based on space weather.

- This model successfully explains why auroras can flare up suddenly even when the background energy conditions seem relatively calm.

Sources & Further Reading

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What are Alfvén waves?

A: Alfvén waves are a type of electromagnetic wave that travels along magnetic field lines in a plasma. You can think of them like a vibration traveling down a guitar string, except the ‘string’ is one of Earth’s magnetic field lines, and the ‘vibration’ is carrying electrical current and energy that powers the aurora.

Q: So the falling electrons ARE the aurora?

A: Yes and no. The light of the aurora is produced when falling electrons strike atmospheric gases. But this research shows their *other* job is just as important: they change the conductivity of the atmosphere, which allows the *entire system* that accelerates them to become more powerful and unstable.

Q: Why is a ‘threshold’ so important?

A: A threshold explains why auroral displays aren’t constant. They can remain calm for a long time and then suddenly erupt. The system has to build up enough energy to cross that tipping point, and this research shows that electron precipitation effectively lowers the bar, making those eruptions happen more easily.

When are northern lights today?

How Can I See the Northern Lights Tonight? A Forecasting Guide

The desire to see the Northern Lights ‘tonight’ is a common and exciting one. While the aurora isn’t predictable with the same certainty as tomorrow’s sunrise, modern space weather forecasting gives us powerful tools to dramatically increase our chances. It’s not about luck; it’s about knowing what to look for.

This guide will walk you through the three essential ingredients you need for a successful aurora hunt and introduce you to the key forecasting tools the experts use. By understanding these basics, you can turn a hopeful glance at the sky into a calculated and often rewarding viewing experience.

The Three Essential Ingredients for an Aurora Sighting

Seeing the aurora requires a perfect alignment of conditions both in space and on the ground. If you are missing any one of these three key elements, you won’t see the show, no matter how strong the solar storm is.

1. Complete Darkness

The aurora is a relatively faint phenomenon, easily washed out by other light sources. First, you need it to be dark in the sky, which means waiting until at least 1.5 to 2 hours after sunset, a period known as astronomical twilight. Second, you must get away from light pollution from cities and towns. Even a distant city can create a ‘sky glow’ on the horizon that can be mistaken for, or hide, a faint aurora. Use a light pollution map online to find the darkest possible viewing locations near you. The phase of the moon also matters; a bright full moon can make it harder to see fainter displays, while a new moon provides the ideal dark canvas for the aurora to shine.

2. Clear, Cloudless Skies

This may seem obvious, but it’s the most common reason for a failed aurora hunt. The Northern Lights occur in the thermosphere, between 60 to 200 miles (100-320 km) above the Earth’s surface. Clouds, on the other hand, form in the troposphere, just a few miles up. This means any significant cloud cover will completely block your view of the aurora above. Before you head out, always check your local weather forecast, paying close attention to the cloud cover forecast for the specific hours you plan to be watching. Satellite imagery apps can be particularly helpful for seeing where cloud banks are in real-time and finding potential clear patches.

3. High Auroral Activity (Geomagnetic Storm)

This is the ‘space weather’ component. Auroral activity is measured on a scale called the Kp-index, which runs from 0 (very calm) to 9 (extreme storm). For those living in the main auroral zone (like northern Alaska, Canada, Iceland, or Scandinavia), a Kp of 2 or 3 might be enough to see something. For viewers in the mid-latitudes (e.g., northern United States, UK, central Europe), you typically need a Kp-index of at least 4 or 5 to see the aurora, and even then, it will likely be a faint glow on the northern horizon. A Kp of 6 or 7 indicates a strong storm that could bring the lights much further south, making them brighter and more dynamic for everyone.

Your Aurora Forecasting Toolkit

Once you’ve confirmed dark and clear skies are likely, it’s time to check the space weather forecast using a few key data points.

The Kp-Index Forecast

The Kp-index is the single most important number to watch. Websites like NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center and apps like SpaceWeatherLive provide a short-term Kp forecast, usually for the next 24-48 hours. This forecast is broken down into 3-hour blocks. Look for periods where the predicted Kp is highest during your local nighttime hours. Remember, this is a planetary index, so it’s the same number no matter where you are. A higher Kp means the auroral oval (the ring of light around the pole) is expanding, pushing the aurora further south and making it visible to more people. Many apps allow you to set alerts for when the Kp-index reaches a certain level.

Real-Time Solar Wind Data

For the most accurate, up-to-the-minute forecast, advanced chasers look at real-time solar wind data from satellites. The most critical value is Bz (pronounced ‘B-sub-Z’). When the Bz value is negative (pointing south), it effectively ‘opens a door’ in Earth’s magnetic field, allowing solar wind energy to pour in and fuel the aurora. A sustained negative Bz is the best indicator that an aurora is imminent or in progress. Other important values are Speed (faster is better, over 500 km/s is great) and Density (more particles mean more potential light). A strong negative Bz combined with high speed and density is the perfect recipe for a spectacular show.

Quick Facts

- You need three things to see the aurora: darkness, clear skies, and high geomagnetic activity.

- The Kp-index measures auroral strength on a scale of 0 to 9.

- For mid-latitudes (e.g., northern US/UK), you generally need a Kp-index of 4 or 5, at minimum.

- Forecasts are most reliable in the short term; check the 30-60 minute forecast for the best accuracy.

- The solar wind’s ‘Bz’ value must be negative (southward) to effectively trigger an aurora.

- Use light pollution maps to find dark viewing spots away from city glow.

- Aurora forecast apps can send you push notifications when activity levels are high.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What Kp-index do I need to see the aurora? A: It depends on your location. Inside the auroral oval (e.g., Iceland, Fairbanks), a Kp of 2-3 is often visible. For mid-latitudes (e.g., Seattle, Glasgow), you’ll likely need a Kp of 4-5 for a horizon glow and Kp 6+ for overhead displays.

Q: How long does an aurora display last? A: It varies greatly. A display can be a brief ‘substorm’ lasting only 10-20 minutes, or it can be an ongoing event that waxes and wanes for several hours. It’s best to be patient and stay out for at least an hour if activity is predicted.

Q: Can I see the aurora with a full moon? A: Yes, but the bright moonlight will wash out fainter auroras, making them much harder to see and photograph. A very strong display (Kp 6+) can still be spectacular with a full moon, but a new moon always provides the best viewing conditions.

Q: What direction should I look to see the Northern Lights? A: Unless you are in the far north, you should always start by looking toward the **northern horizon**. The aurora often begins as a faint, greyish-green arc in the north. If the storm is very strong, it may expand to fill the entire sky.

Other Books

- NOAA SWPC – Aurora 30-Minute Forecast

- SpaceWeatherLive – Real-Time Solar Wind Data

- Light Pollution Map

Hubble's Aurora Hunt: Our Cosmic Shield Detector

Summary

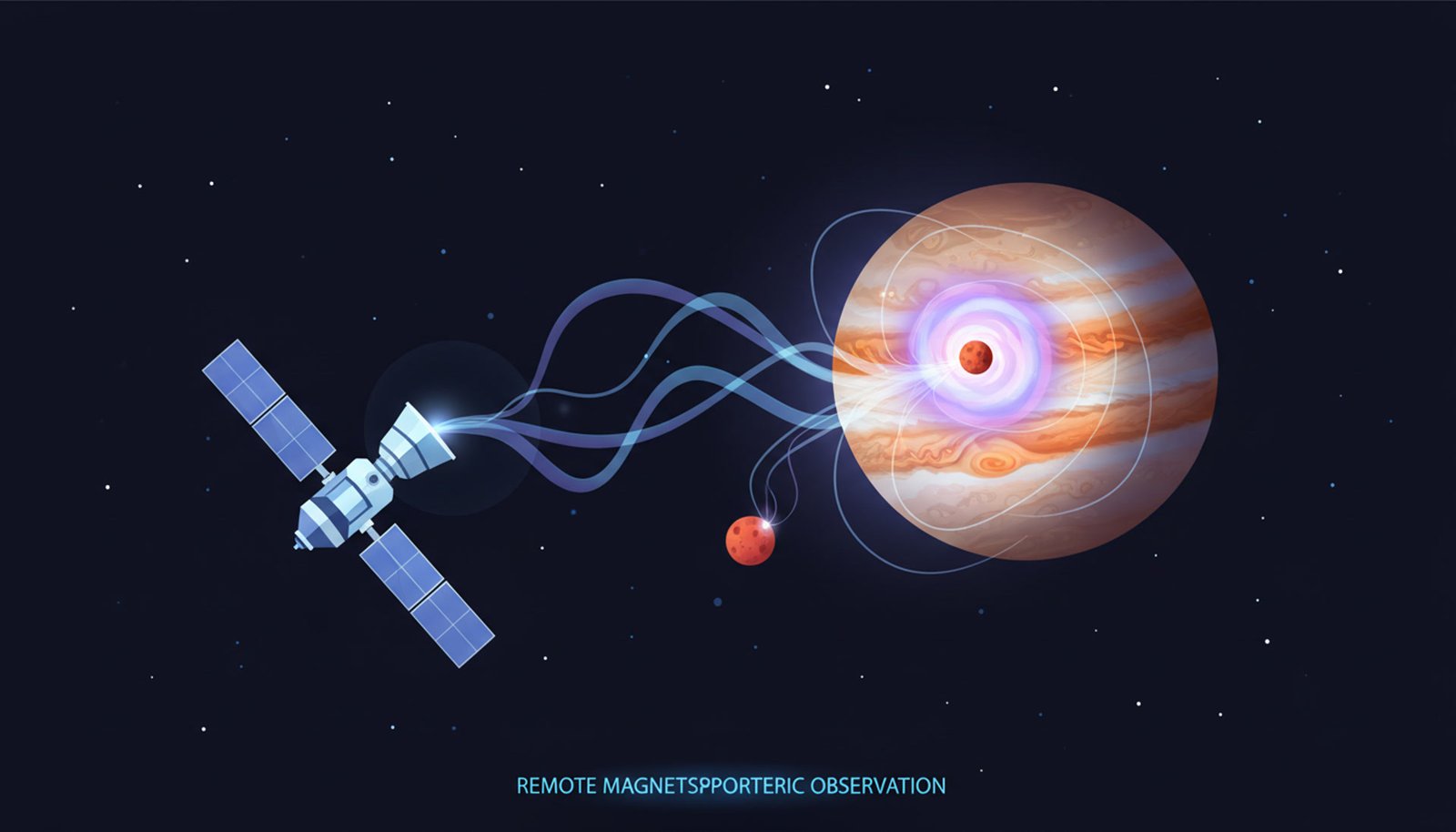

By the end of this article, you will understand how scientists use the Hubble Space Telescope to read the ‘light shows’ on giant planets, and how these auroras act as a powerful diagnostic tool for invisible magnetic fields and dangerous space weather.

Quick Facts

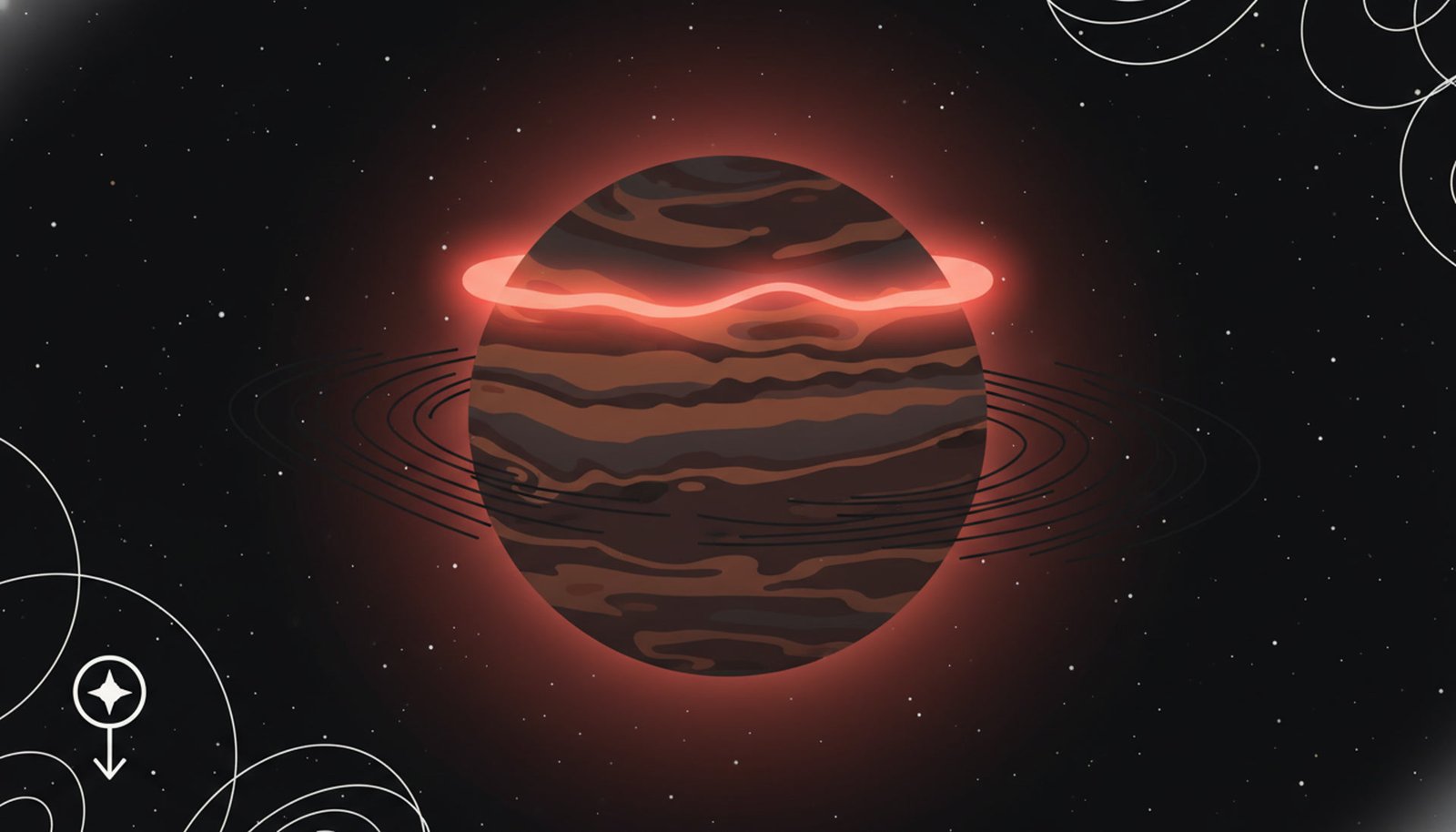

- Uranus's magnetic field is so tilted and off-center that its magnetosphere 'tumbles' as it rotates.

- Moons like Io and Ganymede create their own personal auroral 'footprints' on Jupiter's atmosphere.

- To see the full picture, scientists need two views at once: Hubble's 'big picture' from far away and a probe like Juno's 'close-up' from inside the system.

- Uranus's aurora is so faint that astronomers had to schedule Hubble's observations to coincide with solar storms hitting the planet.

- Unlike Earth's green auroras (from oxygen), Jupiter and Saturn's are mainly ultraviolet, caused by hydrogen.

The Discovery: The Perfect Cosmic Team-Up

For years, scientists have paired the Hubble Space Telescope with deep space probes for a one-two punch of discovery. The Story is one of perfect synergy: a probe like Cassini orbiting Saturn gets ‘in the mud’, measuring particles and magnetic fields up close, but it’s too close to see the whole picture. At the same time, Hubble, from its distant perch, captures the entire auroral oval in a single snapshot. By combining these two views, scientists can directly link a specific storm in the solar wind or a change in the magnetotail to a visible flare-up in the aurora. This paper highlights a unique opportunity in 2016-2017 when the Cassini mission at Saturn and the new Juno mission at Jupiter were both in their prime, creating a ‘Grand Finale’ of comparative studies.

Read the Original ‘White paper submitted in response to the HST 2020 vision call’

Such synergistic observations proved to be essential to assess complex magnetospheric processes.

— L. Lamy et al.

The Science Explained Simply

An aurora is NOT like a neon sign that is simply switched on. It is a dynamic process. It begins when charged particles—from the solar wind or a volcanic moon like Io—get trapped in a planet’s magnetic field. This field, like an invisible funnel, channels these high-energy particles toward the poles. As they accelerate down the magnetic field lines, they violently collide with gas in the upper atmosphere (like hydrogen on Jupiter). This collision excites the gas, causing it to glow. So, the aurora is a direct visual trace of where energy is being dumped into a planet’s atmosphere. Let’s build a fence: this is fundamentally different from a planet just reflecting sunlight. This is light the planet is *creating* itself in response to its space environment.

The Aurora Connection

Auroras are the best window we have into a planet’s magnetosphere—its protective magnetic shield. On Earth, this shield deflects the harmful solar wind, protecting our atmosphere and enabling life. Giant planets have magnetospheres thousands of times stronger. The size, shape, and brightness of their auroras tell us exactly how that shield is interacting with the solar wind, its own moons, and its rapid rotation. The Salient Idea is that by studying the ‘weird’ auroras of a planet like Uranus, with its tumbling magnetic field, we learn about the fundamental physics that governs all magnetic fields, including the one that keeps us safe here on Earth. They are cosmic laboratories for space weather.

Aurorae are therefore a direct, powerful, diagnosis of the electrodynamic interaction between planetary atmospheres, magnetospheres, moons and the solar wind.

— L. Lamy et al.

A Peek Inside the Research

Getting these images isn’t easy; it’s a testament to Knowledge and Tools. Scientists use specialized instruments on Hubble like STIS (Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph) that can see in Far-Ultraviolet (FUV) light, which is invisible to our eyes but where hydrogen auroras shine brightest. The real challenge comes with the ice giants. The paper describes the difficult hunt for Uranus’s aurora. After failed attempts, they realized the emissions were too faint to see under normal conditions. Their solution was clever: they used models to predict when a solar storm (an interplanetary shock) would hit Uranus, and scheduled Hubble’s precious time to observe right then, maximizing their chances of seeing the aurora flare up. This shows research is not just pointing and shooting; it’s a game of strategy and prediction.

Key Takeaways

- Auroras are visual fingerprints of a planet's invisible magnetosphere.

- Comparing different planets (Jupiter vs. Uranus) reveals universal rules of plasma physics.

- The Hubble Space Telescope is currently our most powerful tool for observing alien auroras in ultraviolet light.

- Combining remote (HST) and in-situ (space probes) data is the gold standard for planetary science.

- Studying other magnetospheres helps us understand the dynamics of Earth's own protective magnetic shield.

Sources & Further Reading

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why can’t probes like Juno just take pictures of the whole aurora?

A: A probe like Juno flies very close to the planet. It’s like trying to take a picture of an entire football stadium while standing on the field. You get incredible detail of the grass and players near you, but you can’t see the whole game at once. Hubble provides that wide, contextual view from the nosebleed seats.

Q: Are auroras on other planets different colors?

A: Absolutely! The color of an aurora depends on what gas is being excited in the atmosphere. Earth’s are famously green and red from oxygen and nitrogen. Jupiter and Saturn’s atmospheres are mostly hydrogen, so their main auroras glow in pink and ultraviolet, which our eyes can’t see without special instruments.

Q: Do planets without magnetic fields have auroras?

A: Generally, no. A strong, global magnetic field is the key ingredient for creating the distinct auroral ovals at the poles. Planets like Venus and Mars lack this shield, so while they have some high-altitude ‘airglow’, they do not have the structured, powerful auroras we see on Earth or the giant planets.

How much is northern lights tour in Iceland?

How Much Does a Northern Lights Tour in Iceland Cost?

Seeing the Aurora Borealis dance across the Icelandic sky is a bucket-list dream for many travelers. But what does this magical experience actually cost? The price of a Northern Lights tour in Iceland can vary significantly, so understanding the options is key to planning your budget.

This guide breaks down the different types of tours available, their typical price ranges, and the factors that influence the final cost. Whether you’re looking for a budget-friendly excursion or a once-in-a-lifetime private adventure, we’ll help you understand what to expect.

Breaking Down the Costs: Tour Types & Price Ranges

The single biggest factor determining the price of your tour is the type of vehicle you’re in and the size of your group. Each option offers a different balance of cost, comfort, and flexibility.

Budget-Friendly: Large Bus Tours ($50 – $90 USD)

Large coach tours are the most common and most affordable way to hunt for the aurora. These tours accommodate 40-70 passengers and follow a set route to known viewing spots away from city lights. The primary advantage is the low cost. The main disadvantages are the large crowds, limited personal interaction with the guide, and less flexibility to change locations quickly if conditions are poor. A significant perk offered by most bus tour operators is a ‘free retry’ policy: if you don’t see the Northern Lights on your tour, you can join again on another night for free. This makes it a low-risk option for budget-conscious travelers.

Mid-Range: Small Group & Minibus Tours ($90 – $150 USD)

For a more personal and comfortable experience, small group tours using a minibus or van are an excellent mid-range choice. With group sizes typically under 20 people, there’s more opportunity to ask the guide questions and less time spent getting on and off the vehicle. These tours are more agile and flexible, able to change plans and chase clear skies more effectively than a large coach. Many operators also include complimentary hot chocolate and Icelandic snacks, and some may even provide tripods for photography. This option strikes a great balance between cost and a quality viewing experience.

Premium Experience: Super Jeep & Private Tours ($150 – $500+ USD)

For the ultimate adventure, super jeep and private tours offer unparalleled access and exclusivity. Super jeeps are heavily modified 4×4 vehicles with massive tires, capable of navigating rough, snowy terrain to reach remote locations inaccessible to buses. This means you’ll be far from any crowds. A private tour gives you complete control over the itinerary and the guide’s undivided attention. While these are the most expensive options, they provide the most intimate and unique aurora hunting experience, often including professional photography assistance and premium refreshments. The price for a super jeep tour is per person, while private tours are usually a flat rate for the vehicle.

Other Factors That Influence the Final Price

Beyond the tour type, a few other variables can affect the overall cost and value of your Northern Lights excursion.

Tour Duration and Inclusions

Most standard Northern Lights hunts last between 3 to 5 hours, including travel time to and from your pickup point in Reykjavík. Longer, more specialized tours will naturally cost more. Always check what’s included in the price. A basic tour includes transportation and a guide. Mid-range and premium tours might add warm overalls, crampons for icy conditions, hot drinks, snacks, or even professional photos of you with the aurora. These inclusions can add significant value, as renting winter gear separately can be expensive. Always read the tour description carefully to avoid unexpected costs.

Combination Tours

A popular way to maximize your time and budget is to book a combination tour. These packages pair a Northern Lights hunt with another popular Icelandic activity. For example, you might find tours that include an afternoon visit to the Golden Circle, a relaxing evening at the Sky Lagoon or Blue Lagoon, or even an ATV adventure before heading out for the aurora hunt. While the upfront cost is higher than a standalone aurora tour, these combos often offer a better overall value than booking each activity separately. This is a great option if your time in Iceland is limited.

Quick Facts

- Large bus tours are the cheapest option, typically costing $50-$90 USD.

- Small group minibus tours offer a better experience for a mid-range price of $90-$150 USD.

- Super jeep and private tours provide the most exclusive experience, costing $150 to over $500.

- Most standard aurora tours last between 3 and 5 hours.

- Many budget tours offer a ‘free retry’ policy if the Northern Lights are not seen.

- The price often reflects group size, vehicle capability, and included extras like hot drinks or photos.

- Combination tours that pair the aurora hunt with another activity can offer good value.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Is a more expensive tour guaranteed to see the Northern Lights? A: No, seeing the aurora is never guaranteed as it’s a natural phenomenon dependent on solar activity and clear skies. However, more expensive small-group or super jeep tours have experienced guides and the flexibility to travel further to chase clear weather, which can increase your chances.

Q: What is usually included in a basic tour price? A: A basic tour price almost always includes pickup and drop-off from a designated location in Reykjavík, transportation in the tour vehicle, and the services of an expert guide. Warm clothing, food, and drinks are not typically included at the lowest price point.

Q: Should I just rent a car and hunt for them myself? A: Renting a car is an option, but it’s only recommended if you are very confident driving in Iceland’s potentially treacherous winter conditions (ice, snow, high winds). Tour guides are experts at interpreting weather and aurora forecasts, know the safest roads, and can take you to the best dark-sky locations, which can be difficult to find on your own.

Other Books

- Guide to Iceland – Northern Lights Tours

- Visit Iceland – The Official Tourism Information Site

- Lonely Planet – Tips for Seeing the Northern Lights in Iceland

The Magnetic Key to Earth's Shield

Summary

By the end of this article, you will understand how the direction of the interplanetary magnetic field (IMF) acts like a key, either locking Earth’s magnetic shield tight or opening cosmic highways for solar particles to create auroras.

Quick Facts

- Störmer's original theory from 1907 described 'forbidden zones' that particles couldn't enter.

- A southward IMF can create interconnected magnetic field lines—a direct path from interplanetary space to Earth's polar caps.

- A northward IMF actually strengthens Earth's shield, making it harder for particles to get in and trapping existing particles more securely.

- The concept is visualized as a 3D 'potential landscape' where particles are like beads rolling around. A southward IMF carves a new valley into this landscape.

- This theory helps explain why auroras are so much more intense when the interplanetary magnetic field is oriented southward.

The Discovery: Updating a Century-Old Map

In 1907, Carl Störmer created a mathematical map for charged particles moving around Earth. His theory showed there were ‘allowed’ and ‘forbidden’ zones, explaining why some cosmic rays could reach us and others were deflected. But his model treated Earth’s magnetic field in isolation. The Story of this research is how J.F. Lemaire updated that map by adding one crucial detail: the Interplanetary Magnetic Field (IMF) carried by the solar wind. Lemaire showed that when the IMF points southward, it fundamentally changes the rules. It lowers the energy barriers and creates ‘interconnected’ pathways, allowing solar particles to flow into regions that were previously forbidden. This solved the long-standing problem of how auroral electrons could so effectively penetrate our defenses.

A southward turning of the IMF orientation makes it easier for Solar Energetic Particle and Galactic Cosmic Rays to enter into the inner part of the geomagnetic field.

— J.F. Lemaire, The Author

The Science Explained Simply

Imagine the space around Earth as a mountainous landscape of magnetic potential. In Störmer’s original theory, trapped particles, like those in the Van Allen belts, are stuck in a deep, closed-off valley called the ‘Thalweg’. To get in or out, a particle needs enough energy to climb over the high mountain pass. Now, let’s build a fence around this concept. This isn’t just about magnetic field lines guiding particles. It’s about an energy barrier. The Salient Idea is that a southward IMF doesn’t just nudge the particles; it lowers the entire mountain pass. Suddenly, particles with much lower energy can stream into the valley from interplanetary space, or escape from it. A northward IMF does the opposite: it raises the pass, locking the door even tighter.

The ‘pass’ between the inner and outer allowed zones opens up, when -F increases.

— J.F. Lemaire, The Author

The Aurora Connection

The aurora is the result of energetic particles from the sun hitting our upper atmosphere. But how do they get there? Lemaire’s work provides the answer. A southward IMF creates what he calls ‘interconnected magnetic field lines.’ Think of these as direct highways leading from the solar wind, over the lowered ‘mountain pass,’ and down into the polar regions (the cusps). Particles can then spiral freely down these highways without needing to overcome a huge energy barrier. This is why aurora forecasts are so dependent on the ‘Bz’ component of the IMF. A negative Bz (southward) means the cosmic highways are open for business, leading to a much higher chance of vibrant auroras.

A Peek Inside the Research

Instead of relying on massive, computer-intensive simulations that trace billions of individual particles, this study used a powerful analytical approach. Lemaire extended Störmer’s original mathematical framework, which assumed perfect cylindrical symmetry. By adding a uniform north-south magnetic field, he could derive a new, simple equation for the ‘Störmer potential.’ This elegant mathematical work allowed him to see the big picture: how the entire topology of allowed and forbidden zones shifts. It’s a prime example of how a deep understanding of the underlying physics and clever mathematics can reveal fundamental truths that might be missed in the complexity of a full simulation.

Key Takeaways

- Earth's magnetic field isn't a static shield; it's dynamically influenced by the Sun's magnetic field.

- The direction (north/south) of the Interplanetary Magnetic Field (IMF) is more important than its strength for particle entry.

- Störmer's theory was expanded to include the IMF, solving a century-old puzzle about particle access.

- A southward IMF lowers the 'geomagnetic cut-off,' allowing lower-energy particles to penetrate deeper into the magnetosphere.

- This model explains the entry mechanism for particles that cause strong auroras and populate the radiation belts.

Sources & Further Reading

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What happens when the IMF is pointing northward?

A: When the IMF is northward, the magnetic ‘mountain pass’ gets higher. This makes it much harder for solar particles to enter the inner magnetosphere and makes it more difficult for particles already trapped in the radiation belts to escape.

Q: Is Störmer’s original theory wrong then?

A: No, it’s not wrong, just incomplete for describing real-world space weather. It’s a foundational model that works perfectly for a pure dipole magnetic field. Lemaire’s work is an extension that adds another layer of reality—the external IMF—to make it more accurate.

Q: Does this apply to other planets?

A: Absolutely! Any planet with a significant magnetic field, like Jupiter or Saturn, will experience similar effects. The interaction between their magnetospheres and the solar wind’s IMF will determine how particles get in and create their own massive auroras.

How to see northern lights tonight?

How Can I See the Northern Lights Tonight? A Step-by-Step Guide

The idea of seeing the Northern Lights ‘tonight’ is thrilling, turning a regular evening into a potential celestial adventure. While seeing the aurora always involves a bit of luck, you can dramatically increase your chances by being prepared. It’s not about just looking up; it’s about knowing when and where to look.

This guide provides a simple, actionable checklist to follow. By understanding the key factors—space weather, local weather, and location—you can transform from a hopeful sky-gazer into a strategic aurora hunter and give yourself the best possible shot at witnessing nature’s greatest light show.

Your 3-Step Checklist for Tonight's Aurora Hunt

Success in seeing the aurora tonight hinges on three critical checks. If any one of these fails, your chances drop to nearly zero. Follow these steps in order to know if it’s worth heading out.

Step 1: Check the Aurora Forecast

The aurora’s strength is driven by solar activity, which is measured on a scale called the Kp-index, from 0 (calm) to 9 (extreme geomagnetic storm). For most locations in the northern United States or southern Canada, you’ll need a Kp-index of at least 4 or 5 to see anything. For prime aurora-viewing regions like Alaska, Iceland, or northern Scandinavia, a Kp of 2 or 3 can be sufficient. Use a reliable source like the NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center or a dedicated aurora forecasting app. These services provide short-term forecasts (30-90 minutes) that are crucial for ‘tonight’ viewing. A high Kp forecast is your green light to proceed to the next step.

Step 2: Check the Local Weather Forecast

This step is just as important as the first. An amazing Kp-9 storm is happening, but if your sky is covered in a thick blanket of clouds, you won’t see a thing. The aurora occurs far above the clouds, at altitudes of 60 to 200 miles (100-320 km). You need clear or mostly clear skies to see it. Check your local weather forecast specifically for cloud cover percentage. Look for large patches of clear sky, especially on the northern horizon. Satellite imagery apps can be very helpful for visualizing where the cloud breaks might occur. If the sky is overcast, it’s better to wait for another night.

Step 3: Escape the City Lights

The aurora can be very faint, and the glow from cities, known as light pollution, will easily wash it out. You must get as far away from urban centers as possible. Use a light pollution map online to find ‘dark sky’ locations near you. These are often state or national parks, rural roads, or conservation areas. Your ideal spot has an unobstructed view to the north, as the aurora often begins as a low arc on the northern horizon. Even a small town can create enough light to obscure a faint display, so the darker your location, the better your chances of seeing the subtle colors and movements of the lights.

Essential Tips for a Successful Viewing

Once the forecasts look promising and you’ve chosen your spot, a few extra preparations can make the difference between a frustrating night and a magical one.

When and Where to Look

The most active period for auroras is typically during solar midnight, which is usually between 10 PM and 2 AM local time. While strong storms can produce auroras earlier or later, this window is your best bet. When you arrive at your dark location, face north. For viewers at lower latitudes, the aurora may just appear as a faint, greenish glow or pillars of light low on the horizon. Don’t expect the sky to erupt in color immediately. Be patient and scan the northern sky continuously. Sometimes what you think is a faint cloud is actually the beginning of an auroral arc.

Let Your Eyes Adjust to the Dark

Your eyes need time to become sensitive to low light. It can take 20 to 30 minutes for your pupils to fully dilate and for you to achieve ‘night vision’. During this time, you must avoid looking at bright lights, especially your phone screen. The white light from a screen will instantly reset your night vision. If you need a light, use a headlamp with a red-light mode, as red light has a minimal impact on your dark adaptation. This single tip is crucial, as a faint aurora can be completely invisible until your eyes are fully adjusted.

What to Bring for Comfort and Safety

Aurora hunting often involves standing still in the cold for long periods. Dress in warm layers, much warmer than you think you’ll need. Insulated boots, gloves, a hat, and a winter jacket are essential, even on a seemingly mild night. Bring a thermos with a hot drink to stay warm from the inside. A folding chair or blanket will make waiting more comfortable. If you plan to take pictures, a tripod is non-negotiable for the long exposures required. Finally, let someone know where you are going and when you expect to be back, especially if you are heading to a remote area.

Quick Facts

- You need three things to align: a good aurora forecast (Kp-index), clear skies, and a dark location.

- The Kp-index measures geomagnetic activity; a value of 4 or 5 is often needed for mid-latitudes.

- The aurora happens far above the clouds, so a clear weather forecast is mandatory.

- Use a light pollution map to find a viewing spot far from city lights with an open view to the north.

- The best time to watch is usually between 10 PM and 2 AM local time.

- Allow your eyes at least 20 minutes to fully adapt to the darkness; avoid looking at your phone.

- Dress in very warm layers, bring a hot drink, and use a red-light headlamp to preserve night vision.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What Kp-index do I need to see the aurora from my location? A: This depends entirely on your magnetic latitude. In places like Fairbanks, Alaska or Tromsø, Norway, a Kp of 1-2 is often visible. In the northern US (e.g., Minnesota, Montana), you’ll likely need a Kp of 4-6. For rare sightings further south, a major geomagnetic storm of Kp 7 or higher is required.

Q: Can I see the Northern Lights if there is a full moon? A: Yes, but a bright moon acts like a form of natural light pollution. It can wash out fainter auroras, making them harder to see and photograph. However, a very strong aurora will still be visible, and the moonlight can beautifully illuminate the landscape in your photos.

Q: Will my phone camera be able to capture the Northern Lights? A: Modern high-end smartphones with ‘Night Mode’ can often capture decent photos of the aurora. For best results, mount your phone on a small tripod to keep it perfectly still and use the longest exposure setting available. A dedicated DSLR or mirrorless camera with manual controls will still provide superior quality.

Other Books

- NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center – 30-Minute Aurora Forecast

- Light Pollution Map – Find Dark Skies Near You

- Space.com – How to Photograph the Aurora

Plasma Storms Found in the Northern Lights

Summary

By the end of this article, you will understand how scientists discovered the first direct evidence of ‘cavitating turbulence’—a process where intense plasma waves create dynamic, energy-filled bubbles inside the aurora.

Quick Facts

- This was the first direct proof of this violent plasma process happening naturally anywhere in space or astrophysics.

- The electron beams that create the beautiful aurora are also the power source for these plasma storms.

- The 'plasma bubbles,' known as cavitons, are only a few meters wide but occur hundreds of kilometers up in the atmosphere.

- Scientists used a powerful radar in Norway to listen for the specific 'echoes' these plasma waves produce.

- The key evidence was a unique signal—a 'central peak'—which is the smoking gun for cavitons.

The Discovery: Listening to a Plasma Storm

On a November night in 1999, scientists at the EISCAT radar in Norway were studying an intense aurora. They weren’t just watching the lights; they were probing the plasma high above. Their experiment was designed to detect two types of plasma waves: Langmuir and ion-acoustic. Suddenly, their screens lit up with a pattern that had been theorized but never seen in the wild. They detected strong signals from *both* types of waves at the same altitude and time. Even more telling was a Surprise feature in the ion-acoustic data: a strong, stationary central peak. This specific combination was the predicted ‘fingerprint’ of cavitating Langmuir turbulence. The data showed that the aurora’s electron beam was powerful enough to not just create waves, but to make those waves violently carve out bubbles in the plasma itself.

Original Paper: ‘Cavitating Langmuir Turbulence in the Terrestrial Aurora’

The data presented here are the first direct evidence of cavitating Langmuir turbulence occurring naturally in any space or astrophysical plasma.

— B. Isham et al.

The Science Explained Simply

This process is called ‘cavitating Langmuir turbulence.’ Imagine a powerful beam of auroral electrons shooting through the ionosphere’s plasma. This creates high-frequency energy waves, called Langmuir waves. Now, this is NOT like ripples in a pond. When these waves become incredibly intense, they act like a snowplow, physically pushing the surrounding charged particles out of the way. This creates a temporary, low-density ‘bubble’ or cavity—a caviton. The Langmuir waves then become trapped inside their own bubble, which makes them even stronger, until the whole structure collapses. This is the difference between gentle ‘weak’ turbulence and this violent, self-reinforcing ‘strong’ turbulence.

In its most developed form, this turbulence contains electron Langmuir modes trapped in dynamic density depressions known as cavitons.

— Research Paper Abstract

The Aurora Connection

The Northern Lights are more than just a beautiful display; they are the visible result of Earth’s magnetic field guiding high-energy electrons from the solar wind into our upper atmosphere. These same beams of electrons act as the engine for cavitating turbulence. The aurora provides the ‘pump’ of energy needed to drive plasma waves to their breaking point, where they begin to form cavitons. This discovery shows that the beautiful, dancing curtains of light are also sites of incredibly energetic and complex plasma physics. Understanding this process helps us model space weather and how energy from the sun is deposited into our atmosphere, which can affect satellites and radio communication.

A Peek Inside the Research

This discovery relied on the perfect combination of Tools and Knowledge. The tool was the EISCAT incoherent scatter radar, which can measure the faint echoes from different plasma waves. The knowledge came from the Zakharov equations, a set of theoretical physics equations from the 1970s that describe this exact behavior. The researchers ran computer simulations using these equations, feeding them the plasma conditions measured during the aurora (see Figure 4). The simulated radar signal was a near-perfect match for what they observed in reality (Figure 3), specifically the enhanced ‘shoulders’ and the critical ‘central peak’. This match between observation and simulation turned a strange radar signal into a landmark discovery.

Key Takeaways

- The aurora is a natural laboratory for extreme plasma physics.

- Strong Langmuir turbulence creates temporary, low-density cavities (cavitons) in plasma.

- These cavitons trap high-frequency plasma waves, causing them to intensify until they collapse.

- Simultaneous radar detection of Langmuir and ion-acoustic waves, plus a central peak, is the signature of this process.

- Computer simulations were essential to confirm that the observed radar data matched the theory of cavitation.

Sources & Further Reading

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is ‘Langmuir turbulence’?

A: It’s a type of disturbance that happens in plasma, which is a gas of charged particles. When a beam of electrons passes through it, it can create waves, much like a speedboat creates a wake in water. This paper is about a particularly strong, or ‘cavitating,’ form of this turbulence.

Q: Why is this discovery so important?

A: Scientists had created this effect in labs and predicted it happened in space, but this was the first time they found direct proof of it occurring naturally. It confirms a fundamental theory of plasma physics and shows it happens in places like the aurora, pulsars, and the sun’s corona.

Q: Can we see these ‘cavitons’ with our eyes?

A: No, they are far too small, only a few meters across, and occur in the very thin plasma of the ionosphere hundreds of kilometers up. We can only detect their effects using highly sensitive instruments like the EISCAT radar.

When are northern lights tonight?

How Can I Predict the Northern Lights Tonight?

The question ‘Can I see the Northern Lights tonight?’ is one of the most common, but the answer is never a simple yes or no. Seeing the aurora is a magical experience that depends on a perfect alignment of space weather and Earth’s local weather. It’s not about a set schedule; it’s about knowing what to look for.

This guide will empower you to become your own aurora forecaster. We’ll break down the three essential ingredients you need for a successful viewing and introduce you to the simple, powerful tools that experts use to predict when and where the celestial dance will begin.

The Three Essential Ingredients for an Aurora Sighting

For the Northern Lights to be visible, three distinct conditions must be met simultaneously. If even one of these is missing, your chances of seeing the aurora drop to nearly zero. Think of it as a three-item checklist for your aurora hunt.

1. Strong Geomagnetic Activity (The Aurora Forecast)

The aurora is caused by activity from the sun, and we measure this activity using the Kp-index. This is a global scale from 0 (calm) to 9 (extreme geomagnetic storm). For most people living in the northern United States, UK, or central Europe, a Kp-index of at least 4 or 5 is needed for the aurora to be visible on the horizon. In prime aurora locations like Iceland or northern Norway, a Kp of 1 or 2 can be enough for a good show. You can find the current and predicted Kp-index on websites like NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center or through dedicated mobile apps. A higher Kp-index means a stronger, more dynamic, and more widespread aurora.

2. A Dark, Clear Sky (Weather and Location)

This is the most straightforward but often most frustrating factor. The aurora occurs 60-200 miles up in the atmosphere, far above any clouds. If there is heavy cloud cover, you will not see the lights, no matter how strong the storm is. Always check your local weather forecast for cloud cover predictions for the hours between 10 PM and 2 AM. Additionally, you must escape light pollution. City and even suburban lights create a glow that will wash out all but the most intense auroral displays. Use a light pollution map to find a dark spot with a clear view of the northern horizon, at least a 20-30 minute drive away from any significant light sources.

3. The Right Time of Night (And Year)

While a strong storm can be visible after sunset, the prime viewing window is typically during the darkest part of the night, between 10 PM and 2 AM local time. This is when the sky is at its darkest, allowing your eyes to fully adjust and perceive the aurora’s faint colors. Another factor is the moon phase. A bright full moon acts like a giant source of light pollution, making it much harder to see the aurora’s details and colors. The best nights will always be around the new moon. Seasonally, the best times are during the months surrounding the equinoxes (September-October and March-April), as solar activity often increases during these periods.

Your Aurora Forecasting Toolkit

You don’t have to guess. Several free and powerful tools can give you a clear picture of your chances for any given night. Using a combination of these resources will give you the best possible prediction.

Real-Time Ovation Models

For the most accurate ‘right now’ forecast, nothing beats the aurora ovation models provided by organizations like NOAA. These are maps that show a 30-to-60-minute forecast of the aurora’s current intensity and location. The map displays a glowing green, yellow, and red oval over the polar regions. If you see that oval stretching down over your location on the map, and your skies are clear and dark, you should go outside immediately. This is the single most reliable tool for answering the ‘tonight’ question, as it’s based on real-time data from satellites monitoring the solar wind.

Essential Apps and Websites

Several user-friendly apps and websites consolidate all the necessary data into one place. Apps like My Aurora Forecast & Alerts and Glendale App are popular choices. They provide the current Kp-index, short-term and long-term forecasts, cloud cover maps, and solar wind data. Most importantly, you can set up push notifications that will alert you when the Kp-index reaches a certain level for your location. This means you don’t have to constantly check the data; your phone can tell you when it’s time to head out. Websites like SpaceWeatherLive and NOAA’s SWPC are excellent desktop resources for more detailed data and expert analysis.

Quick Facts

- You need three things to see the aurora: a high Kp-index, dark skies, and clear weather.

- The Kp-index measures geomagnetic activity on a scale of 0-9; a Kp of 4 or higher is often needed for mid-latitudes.

- The best viewing time is typically between 10 PM and 2 AM local time.

- Use NOAA’s 30-minute aurora forecast for the most accurate real-time view of aurora activity.

- City light pollution and a bright full moon can significantly reduce aurora visibility.

- Mobile apps like ‘My Aurora Forecast’ can send you alerts when activity is high.

- Even with a perfect forecast, local cloud cover is the ultimate deciding factor.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What Kp-index do I need to see the aurora from my location? A: This depends entirely on your latitude. In the Arctic Circle (e.g., Tromsø, Fairbanks), a Kp of 1-2 is often visible. In the northern US or UK, you’ll likely need a Kp of 4-6. For rare sightings in mid-latitude states, a major storm of Kp 7 or higher is required.

Q: How reliable are long-term aurora forecasts? A: Forecasts more than 2-3 days out are highly speculative. They are based on observing sunspots that might produce an eruption. The most reliable predictions are within a 24-48 hour window, after a Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) has actually left the sun and is heading toward Earth.

Q: Can I see the Northern Lights in a city? A: It is extremely difficult. City light pollution creates a bright skyglow that will wash out all but the most intense, once-in-a-decade auroral storms. For the best experience, you should always plan to drive to a dark location away from city lights.

Q: Why does my camera see the aurora better than my eyes? A: Camera sensors are more sensitive to light than the human eye. They can use a long exposure (leaving the shutter open for several seconds) to collect more light, revealing vibrant colors and details that may appear as faint, greyish clouds to the naked eye, especially during weaker displays.

Other Books

- NOAA SWPC – Aurora 30-Minute Forecast

- SpaceWeatherLive – Real-time Aurora and Solar Data

- NASA – What is Space Weather?

Earth's Magnetic Shield Breathes

Summary

By the end of this article, you will understand a powerful and simple new way to think about space weather: that Earth’s magnetosphere physically expands and contracts like it’s breathing, and how this simple idea explains the complex relationship between magnetic storms, substorms, and the aurora.

Quick Facts

- Surprise: A substorm, often seen as part of a storm, can actually weaken the main magnetic storm by rapidly releasing energy.

- It takes the auroral oval about 45 minutes to expand after the solar magnetic field turns south, but 8 hours to contract after it turns north.

- The model predicts that during long periods of calm, 'dents' should form on the pre-noon and post-noon sides of our magnetic shield.

- The mysterious 'theta aurora', a glowing bar across the polar cap, can be explained by a severely contracted magnetosphere splitting the magnetotail.

The Discovery: Solving a Cosmic Puzzle

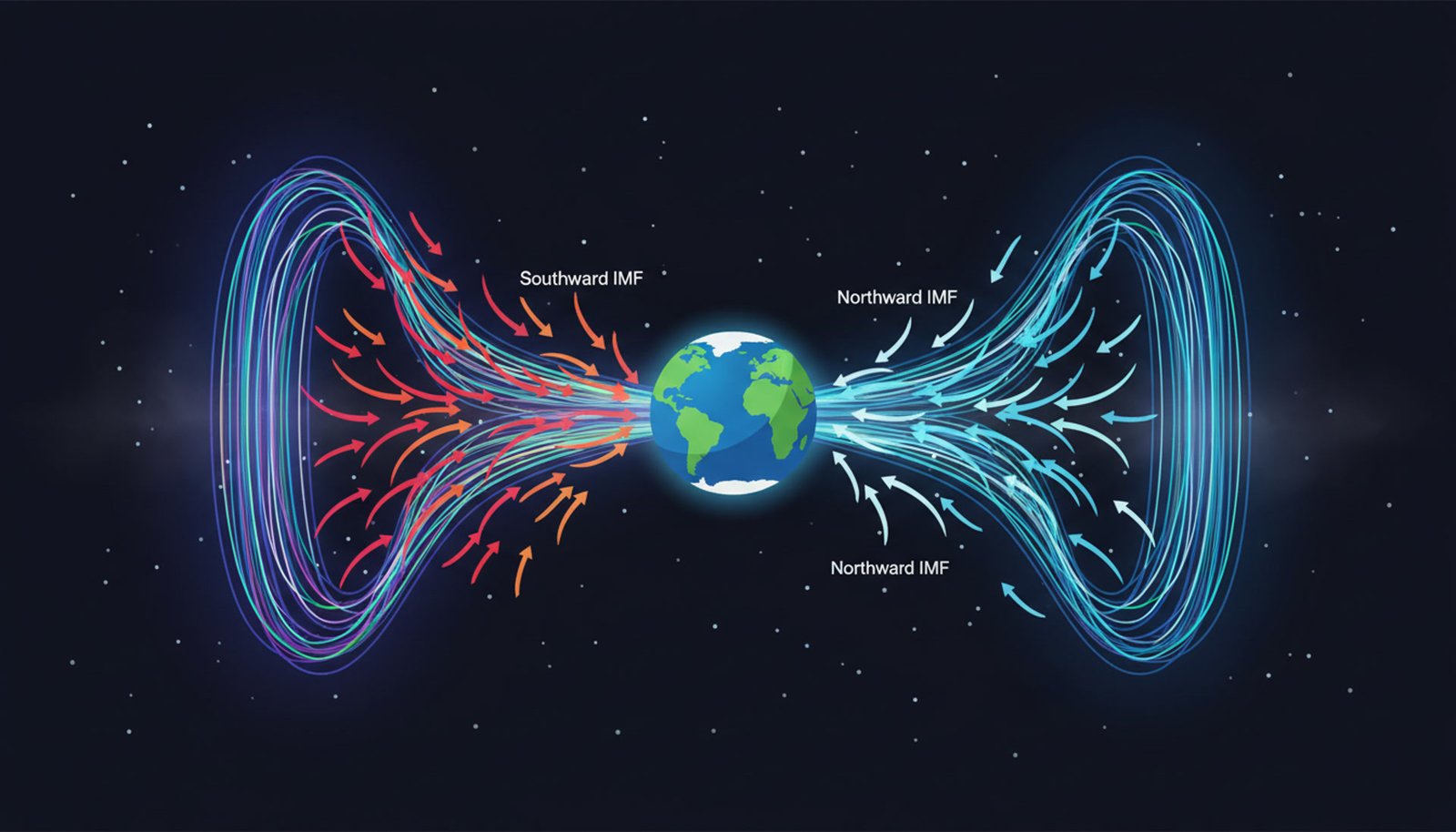

For decades, scientists have used a complex model called ‘magnetic reconnection’ to explain space weather. But some observations never quite fit, like why the main phase of a magnetic storm begins *before* the first substorm, or why substorms can sometimes weaken a storm. This research proposes a simpler Story: what if the magnetosphere behaves like a simple physical object? The paper shows that by treating the interaction as an attraction or repulsion—like two magnets—many of these puzzles disappear. A southward Interplanetary Magnetic Field (IMF) attracts and expands Earth’s field, creating a storm. A northward IMF repels and contracts it. This ‘breathing’ model provides an intuitive framework that matches observations without the theoretical problems of older models.

Original Paper: ‘Magnetic Storm-substorm Relationship and Some Associated Issues’ by E. P. Savov

The expansion (contraction) of magnetosphere accounts for the observed expansion (contraction) of the auroral oval.

— E. P. Savov, Researcher

The Science Explained Simply

Imagine the Sun sends out a magnetic field (the IMF). When the IMF arriving at Earth points south, its field lines align with Earth’s in an attractive way. This pulls Earth’s magnetic shield outward, expanding it and allowing it to capture more energy and particles from the solar wind. This is the ‘growth phase’ of a storm. Now, let’s build a fence: this is NOT the same as ‘magnetic reconnection’ where field lines are thought to break and re-form. Think of it more as a balloon inflating. Conversely, when the IMF points north, the fields repel each other. This squeezes and contracts the magnetosphere, pushing the solar wind away more effectively and leading to calmer space weather. The Salient Idea is that this simple push-and-pull dynamic governs the entire system.

The Aurora Connection

The location of the aurora is a direct visual indicator of this breathing. During a magnetic expansion (southward IMF), the boundaries of the magnetosphere are pushed out, and the auroral oval shifts towards the equator. This is why auroras are seen at lower latitudes during big storms. During a contraction (northward IMF), the oval shrinks back towards the pole. What about a substorm? The model explains the explosive phase as a rapid, partial *contraction* of the over-stretched magnetotail. This contraction violently flings particles back towards Earth, creating the bright, dynamic auroral surges on the poleward edge of the oval. A very strong, prolonged contraction can even bifurcate the magnetotail, creating the rare and beautiful transpolar arc known as a ‘theta aurora’.

A Peek Inside the Research

This isn’t just an idea; it’s backed by calculation and a proposal for a physical test. The author calculated the expected average thickness of the magnetopause boundary layer based on the observed 45-minute expansion and 8-hour contraction times of the aurora. The result, about 0.44 Earth radii, matches spacecraft observations perfectly. To further prove the concept, the paper outlines an upgrade to the famous 19th-century ‘terrella’ experiment. By adding a second large magnetic coil to simulate the IMF, a lab could physically demonstrate the expansion and contraction of the artificial auroral oval by simply flipping the polarity of the external ‘solar’ magnet. This brings a grand cosmic theory down to a testable, hands-on experiment.

The suggested 3D-spiral magnetic reconfiguration… avoids the topological crisis.

— E. P. Savov, on why this model is simpler

Key Takeaways

- Southward IMF acts like an attracting magnet, causing Earth's magnetosphere to expand and create storms.

- Northward IMF acts like a repelling magnet, causing the magnetosphere to contract and become quiet.

- A magnetic storm is just a very large, prolonged expansion of the magnetosphere.

- A substorm's explosive phase is a rapid, partial contraction that releases accumulated energy, creating auroral surges.

Sources & Further Reading

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: So does a substorm cause a magnetic storm?

A: According to this model, no. A magnetic storm is a large expansion of the magnetosphere caused by a long period of southward IMF. A substorm is a smaller expansion (growth phase) followed by a rapid, partial contraction (expansion phase) that releases energy, often weakening the larger storm.

Q: Why is this model better than the old ‘magnetic reconnection’ one?

A: The author argues it’s simpler and avoids certain theoretical problems, a principle known as Occam’s Razor. It explains confusing observations, like the storm-substorm timing, more intuitively by likening the magnetosphere’s behavior to simple magnetic attraction and repulsion.

Q: What happens when the solar wind pressure increases?

A: Higher solar wind pressure pushes on the magnetosphere, creating a longer, thicker magnetotail. This thicker tail is better at ‘catching’ the southward IMF, which then drives an even stronger expansion and a more intense magnetic storm.

What is northern lights stone?

What Is Northern Lights Stone? A Guide to Auroral Gems

If you’ve searched for ‘Northern Lights Stone’, you’ve likely seen a variety of beautiful, iridescent gems. However, this isn’t a specific geological classification. It’s a marketing term used to describe any gemstone whose appearance captures the ethereal, shifting colors of the Aurora Borealis. The effect is caused by unique optical properties within the stone, not by pigments or dyes.

While several gems can fall under this umbrella, the name is most famously and accurately associated with one particular mineral family known for its breathtaking play-of-color. This guide will explore the primary stones known as Northern Lights Stone and other contenders for the title.

The Primary 'Northern Lights Stone': Labradorite & Spectrolite

The true origin of the ‘Northern Lights Stone’ name lies with the feldspar mineral Labradorite. Its unique optical phenomenon is so tied to the aurora that it has become the definitive gem for this description.

Labradorite: The Original Aurora Gem

Labradorite is the gemstone most commonly sold as Northern Lights Stone. It is a feldspar mineral that, at first glance, can appear to be a dull, dark grey-green stone. However, when it catches the light at the right angle, it flashes with an incredible iridescent glow of blue, green, gold, and peacock colors. This stunning optical effect is called labradorescence. According to Inuit legend, the Northern Lights were once trapped inside the rocks along the coast of Labrador, and a warrior freed most of them with his spear, but some of the light remained captured within the stone. This folklore perfectly captures the visual magic of Labradorite, making it the quintessential auroral gem.

Spectrolite: Labradorite’s Premium Cousin